Behavior Today Newsletter 39(4)

From the President’s Desk

Timothy Landrum

If you’re like me, and particularly if your professional life revolves around schooling in any form or capacity, you look forward to summertime each year. You do this with the undying hope it brings a break from at least some traditional duties, a more relaxed pace, and time to catch up on some professional and personal tasks you just didn’t have time for during the school year but promised to catch up on once summer arrived and things slowed down. And, if you’re like me, you probably cringed or even laughed out loud before you finished reading the previous sentence.

In my experience, summer is as busy a time as any, yet we persist in thinking, or maybe just naively hoping, that summer will offer a magical time of slower pace, catching up on work, and relaxing. I’ve decided that’s probably a holdover from when we were kids, and summer break was, for some, a true break, involving at minimum sleeping in a little, lots of down time, and at best lots of fun. It’s also possible we just convince ourselves that was true, something social psychologists have called ‘the rosy view’ (Mitchell et al., 1997).

I’m confident most of our members, like our Executive Committee, have been busy all summer, engaged as much or more than they were during the school year. You might be taking or teaching college courses, supervising or teaching summer school, attending or delivering professional development, planning for the upcoming academic year, and of course continuing to provide services and supports for children and families, whose needs are no less intense just because it’s summer.

One of the things DEBH focused on this summer was partnering with state or regional affiliates. We partnered with the Behavior Institute in Kentucky (hosted by KY-CCBD), which included several presentations by our board members and a very successful DEBH-hosted poster session. We also had a presence at Ohio CEC and Ohio CCBD’s Bridges to Inclusion Conference in Cincinnati. and the Summer Symposium on Evidence-based Practices for Students with Autism and EBD in Minneapolis (hosted by MN-CEC and several other partners, including DEBH and DADD). I had the pleasure of speaking in both Kentucky (in person) and Minnesota (virtually), and many members of our Executive Committee also presented at these as well. Shout outs to Brian Barber, Lonna Moline, Jonte’ Taylor (JT), and Staci Zolkoski (and apologies to others I’m missing).

We have several goals in these partnerships, not the least of which is simply supporting these state chapters. We want them to sustain and thrive. A perhaps ulterior motive, though, is consistent with one of the tasks I hope our division leadership team will take on in earnest this year: sustaining and growing our own membership. I can’t say this is a new initiative, or that I have answers. CEC and its divisions (like many professional organizations) have all experienced membership declines in recent years, and all struggle with this challenge. DEBH is no different, and our Executive Committee continues to discuss ways we can be proactive in these efforts. Indeed, we consider ‘member benefit’—what members want and need from the organization— in virtually every discussion we have as an Executive Committee regarding any activity we might engage in. Partnering with state chapters, we thought, would be one small way of connecting ‘national’ DEBH more directly with members in a tangible way.

There are many issues to consider with regard to membership. One question I think about a lot is the difference between sustaining membership and growing membership. Current members are with us for a reason, and I hope you all stay with us. But what are the reasons members stay? Are you satisfied with what the organization is doing for you, or on behalf of children and youth with or at risk for EBD? Are there specific services, supports, resources, PD opportunities, or advocacy efforts that are important to you? That is NOT a rhetorical question; I’d love to hear from you directly ([email protected]), as would any member of our executive committee.

Separate from our current members, we’d of course love to welcome new (or returning) members. The same questions apply: what benefits (services, supports, resources) do we offer, or could we offer, that would be attractive enough to professionals to encourage them to join DEBH? If you’re reading this, chances are good you’re already a member. Would you encourage your colleagues, co-workers, or students to join? What reasons would you give them?

Yet another angle is that our members, and those we would like to become members, fill many and sometimes multiple professional roles, and include teachers, paraprofessionals, behavior analysts, support specialists, administrators, school psychologists, higher ed faculty, and undergraduate and graduate students, to name only a few. How do their needs differ, and can we target activities or resources better to meet their needs? Again, we welcome feedback and input from anyone, members and non-members, on how we might better meet our mission.

In short, we want to be the premier professional organization that provides information, advocacy, and support for children and youth with or at risk for EBD, and the professionals who serve them. If parents, professionals, policymakers, or student or faculty members in higher ed have questions or a need for information about any aspect of services and supports for children and youth with EBD, we want to be the first place they look. Again, if you are a current member, I’d love to hear what it is about DEBH that keeps you around (think of it as behavior specific praise for the organization). I’ll end by adding my personal take on what keeps me around: it’s being part of a professional organization and community that shares common goals about supporting kids with EBD, their families, and the professionals who serve them. The intangibles of being part of a professional community and the networking it offers have been invaluable to me, and yes—these intangibles have led to many tangible benefits and professional opportunities. I’ve been a member as a teacher, as a student, and now as a faculty member in higher ed, and I’ve never regretted or even questioned why I was a member. I suspect this is true of many current members, but my goal this year is to make these same sentiments ring true for even more current and potential members. Again, let us know if you any thoughts on how we can get there.

Reference

Mitchell, T. R., Thompson, L., Peterson, E., & Cronk, R. (1997). Temporal adjustments in the evaluation of events: The “Rosy View.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 421-448.

Foundation New Fall 2022

Lonna Moline

Happy Fall from Lonna Moline, current President of DEBH Foundation

Looking for some financial support? We offer academic scholarships and professional grants to support practitioners working with students with emotional and behavioral challenges. Which one will help support and advance your professional career?

Dr. C. Michael Nelson Professional Development Support

The purpose of this grant is to encourage the professional development of all persons involved in providing education or related services to children and youth with emotional or behavioral disorders (E/BD) consistent with the mission of DEBH. The Foundation will provide funding up to $500 to enable practitioners to attend professional development activities that are supported by DEBH (e.g., TECBD, CEC conferences).

Dr. Frank Wood Practitioner Grant

The purpose of this grant is to recognize the professional application of knowledge and skills to improve academic, social, emotional, and community employment-based outcomes for children and youth with challenging behaviors. The DEBH Foundation will award funding of up to $500 to implement a high-quality practice or program that directly serves students in their educational setting.

Academic Scholarships

Dr. Eleanor Guetzloe - Undergraduate Scholarship

Dr. Douglas Cheney - Graduate Scholarship

Dr. Lyndal Bullock - Doctoral Scholarship

The purpose of the Academic Scholarships are to support undergraduate and graduate study in the area of emotional/behavioral disorders. The DEBH Foundation will award a $500 scholarship to one undergraduate, one graduate, and one doctoral student towards educational expenses.

Here are some highlights from a couple of previous academic scholarship recipients:

James Lee, Dr. Lyndal Bullock Scholarship: James is still actively conducting research. His primary focus is on minority and marginalized families of young children with autism. He graduated with a doctorate in special education from the UIUC. He is completing the first year of IES funded postdoc under Dr. Brian Boyd at the Juniper Gardens Children’s Project at KU. He will be moving into a faculty position in 2022.

Allyson Pitzel, Dr. Lyndal bullock Scholarship: Allyson is in her third year as a doctoral student and preparing for her dissertation. Her dissertation will center around the application of self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) in writing with integrated and intensified self-determination instruction for girls in a juvenile justice facility.

Since receiving Bullock Award in 2021, she has implemented and assisted with a series of SRSD with self-determination writing studies for youth with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) in the juvenile justice system (e.g., iPad vs. paper/pencil prompts; choice in prompt topic vs. no choice in prompt topic). These studies have focused on teaching youth how to use writing as a way to self-advocate for things they want or need - both inside and outside of the facility. Results demonstrated improvement in writing performance (e.g., increase in essay elements written) and self-determination (e.g., self-advocacy, self-efficacy).

She has also worked with a research team to extend SRSD with self-determination instruction into reading for youth with EBD in the juvenile justice system. They are in the process of wrapping up their first reading study where youth were taught how to find the main idea and details in a passage using SRSD with self-determination instruction (e.g., choice in passage topic vs. no choice in passage topic). This is the first of several studies planned to improve the reading skills of youth in restrictive education settings.

Allyson is passionate about continuing to implement SRSD with self-determination instruction into restrictive education settings to improve the reading and writing skills of youth with EBD. She looks forward to what the future holds.

Looking forward to seeing YOUR application! Email [email protected] to get more details. Deadline is December 9,2022. Awardees will be notified in late January 2023.

In A Major Way:

The Story Behind the Book:

The Mixtape Volume 1: Culturally Sustaining Practices Within MTSS

Featuring the Everlasting Mission of Student Engagement

Jonte’ C. Taylor, Pennsylvania State University

William Hunter, University of Memphis

Laron Scott, University of Virginia

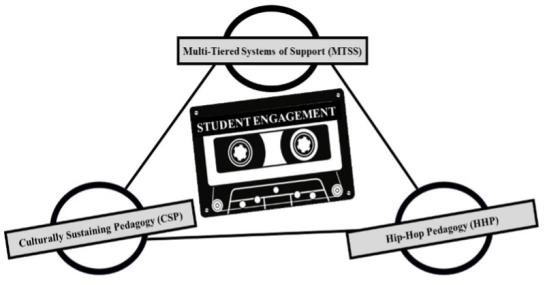

We are pleased to announce, the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) will be publishing the text “The Mixtape Volume 1: Culturally Sustaining Practices Within MTSS Featuring the Everlasting Mission of Student Engagement”. Besides for working to win the longest book title of the year award, we, the editors of the text, have been working on this book diligently for over a year. The genesis of this book was stirred through our a) collective love for Hip-Hop culture, b) belief in culturally responsive pedagogy, and c) desire to provide the CEC community of teachers and researchers with a resource to help students who are often marginalized. Students with disabilities can often be a marginalized group, when compounded with racial, ethnic, gender/sexual, and/or social class intersections, the potential for these students to be underserved or exposed to abuse is exponential. As three black males in a field and in positions in which we rarely see folks that look like us, we wanted to develop a resource that had a keen eye on representation.

When we designed the concept of this book, it was our intent to deliver a novel contribution to the field. We hope this book serves the needs of our students within elementary and secondary communities across the world. Beyond that, we wanted to include as many voices as possible in our pursuit. Consequently, this book features concepts produced by the editors with dope (a Hip-Hop term that means “excellent”) contributions from authors within the field of special education, general education, higher education, social work, counseling, and other disciplines. These authors are classroom teachers, administrators, graduate students, professors, researchers, and more. As diverse as the authorship, the content of the text is equally diverse. The book is divided into multiple sections; however, we want to highlight two major sections of content. The section entitled “Enter the 36 Chambers: Dispositions, Mindsets, and Theories” features chapters connecting Hip-Hop education/concepts with critical theoretical frameworks and topics connected to educational dispositions. We hope that this section inspires educators to better understand ways to promote classrooms that embrace a “community of learners” concept, where high expectations are embedded, and equitable practices are featured. The section entitled “Trill Education: Strategies and Interventions within Multi-Tiered Systems” features chapters embracing real/true education that will have a positive impact on K-12 students from diverse educational backgrounds. We hope this section provides instructional strategies/instruction promoting active K-12 student engagement within MTSS that classroom teachers or practitioners in any setting can implement immediately.

As previously mentioned, CEC has graciously agreed to publish our vision. Along with CEC as our primary organizational affiliation, we further envisioned this text as a tool for members of multiple divisions within CEC. One of those divisions, the Division for Emotional and Behavioral Health (DEBH), was in our thoughts from the beginning. Many of the ideas and strategies are designed to support students’ positive behavior and emotional well-being. We purposely aligned our vision with the mission of DEBH and its membership.

The book will be available soon and we hope that it will be an exciting resource for you to add to your collection.

The Power of Relationships: A Conversation with Dr. Ellen McGinnis Smith

Jim Teagarden & Robert Zabel, Kansas State University

The Janus Oral History Project collects and shares stories from leaders in education of children with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). The project is named after the Roman god, Janus, whose two faces look simultaneously to the past and future. The leaders are asked to reflect on events and people that have influenced their past and have an impact on the future. Ongoing support for the Janus Project is provided by the Midwest Symposium for Leadership in Behavior Disorders (MSLBD). All of the interviews are available in video format at the MSLBD website.

This article features excerpts from the Janus Project conversation with Ellen McGinnis-Smith. A video of the conversation may be accessed here . A transcript of the complete conversation was published in the Intervention In School and Clinic (Zabel et al., 2020).

Dr. McGinnis-Smith has been a special educator for her entire career. She has taught at both elementary and secondary levels, primarily in the area of emotional/behavioral disorders (EBD) and was a consultant in the public schools and for the University of Iowa Department of Child Psychiatry. She was principal of Orchard Place, a residential and day treatment school in Des Moines, Iowa and served as director of special education for the Des Moines Public Schools.

Dr. McGinnis-Smith is co-author of the social skills teaching series, Skillstreaming, co-authored with Richard Simpson Skillstreaming Children and Youth with High Functioning Autism, and Social Skills Success for Students with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism.

Dr. McGinnis-Smith’s passion has been helping educators meet the needs of children and youth with mental health and behavioral concerns.

* * * * *

JANUS: Would you describe your career in the field?

McGinnis-Smith: I spent many years as a teacher in elementary, middle, and high schools. I became a consultant in both public schools and hospital-based programs and then an administrator. I really felt I'd like to support the teachers and the kids. I liked to have the kid contact also, but I really liked supporting the teachers and found teachers could thrive if you helped them learn the skills.

For example, a teacher came to me with an idea from a conference where she heard Larry Brendtro and Martin Brokenleg speak about the power of relationships. She was very interested in their presentation, and I said, "Tell me more." I was intrigued by it and so I talked with some other people. We presented it to the staff and asked, "Do you believe in these things as a staff?" And they said, "This is what we're about. This is a healthy relationship piece.”

When I'd first gone to work in residential treatment, we had to physically restrain quite a bit. I didn't wear jewelry; I didn't wear heels. Then, we ended up implementing the “Circle of Courage” and its Curriculum of Belonging, Mastery, Independence and Generosity (Brendtro et al., 1992). Here were these kids who came into the residential treatment center with all their belongings basically in a garbage bag and yet they would give to others!

We did something we called an “empty bowl.” The kids made ceramics bowls with the art teacher…very wonderful bowls. Then, they put on a soup and bread luncheon for the community, and we'd ask for donations.

The kids thrived. I mean, they just thrived being able to give and donations went to the food bank. Here were kids that didn't have anything, and the thrill they got from giving to others! So, that experience really impacted my career and gave me hope for kids with mental health issues and behavioral disorders.

JANUS: What do you see as the future for the field of educating children with emotional behavior disorders?

McGinnis-Smith: I think people will more likely see kids with behavior disorders having a disability, rather than being naughty, being bad, or willfully disobeying. I think with some of the new things that are coming out, our understanding of trauma, will help that—ranging from suicide prevention to really understanding different diagnoses through what to do. I think it must happen in both special education and general education.

So, I think that will be an area that we certainly need to work on and will change because I don't think that we have a choice. We have to do this in order to work better with kids who have those needs.

JANUS: What advice would you offer practitioners coming into the field?

McGinnis-Smith: My advice would be to focus on relationships first and to build those relationships. I have to describe the relationship as being a healthy relationship, meaning "I believe in you, you can succeed, I know you can do it, I'll be here, I'll support you along the way, “rather than saying "You're my best buddy,” or "I'm going to be your mother,” or whatever.

The relationship I do think is so critical. I think it's hard for some. Some practitioners say, "I know the power of relationships, so I just have to be buddy-buddy with the kids," and that's not healthy. A healthy relationship is, "I will take time for you, I believe in you, and I will help support you and you can do it."

* * * * *

The Janus Project thanks Ellen McGinnis-Smith for her life-long commitment and contributions to students and the people who work with them, her leadership, and for sharing her experiences and insights with the larger field.

References

Brendtro, L. K., Brokenleg, M., & Van Bockern, S. (1992). Reclaiming youth at risk: Our hope for the future. Bloomington, IN: National Education Service.

Zabel, R., Teagarden, J. & Kaff, M. (2020). Building healthy relationships: A conversation with Dr. Ellen McGinnis-Smith. Intervention in School and Clinic, 55 (3), 197-200. DOI:10.117/105345121984226

Policy Guidance on Discipling Students with Disabilities

Mitchell L. Yell, Ph.D.

Students with emotional/behavioral disorders (EBD) are often determined to be eligible for special education services because they exhibit problem behaviors. Such students will often have behavioral programming in their individualized education program (IEP). The most important obligation of special education teachers is to collaboratively develop an individualized program of special education and related services for eligible students with disabilities that confers a free appropriate public education (FAPE).

Specifically, the IDEA requires that “[I]n the case of a child whose behavior impedes the child or that of others, (the IEP team) consider the use of positive behavioral interventions and supports, and other strategies, to address that behavior (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.324 (a)[2][i]).

Students with EBD are often disciplined for inappropriate behavior. In most cases, students with disabilities and students without disabilities are subject to the same school disciplinary code. There are, however, a few notable exceptions. Discipline procedures used with students who are eligible for special education services cannot change their placement nor can the procedures deny them FAPE.

Officials in the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) in the U.S. Department of Education believed that addressing behavior when necessary was so important that they issued a Dear Colleague Letter (DCL) on including positive behavior interventions and supports in the IEPs of students with disabilities. Dear colleague letters from OSEP are policy interpretations of the IDEA and regulations by officials in the U.S. Department of Education. Although policy statements do not have the legal force of either a law or a regulation, they are very important and are often cited in due process hearings.

In the 2016 DCL, OSEP issued the policy statement to clarify that failing to address a student’s problem behavior in his or her IEP could be a denial of FAPE. Additionally, failing to provide behavioral support through the continuum of services, included in the regular education environment, could result in an inappropriately restrictive placement and constitute a denial of placement in the LRE. The 2016 OSEP DCL is a great resource for special educators. The DCL on behavior support can be found by clicking here. (https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/dcl-on-pbis-in-ieps-08-01-2016.pdf)

Language in the DCL, pointed out the statement was part of the Department of Education’s broader work to encourage school environments that are safe, supportive, and conducive to teaching and learning, where educators actively prevent the need for short-term disciplinary removals by actively supporting and responding to behavior…In keeping with this goal, this letter serves to remind school personnel that the authority to implement disciplinary removals does not negate their obligations to consider the implications of the child’s behavioral needs, and the effects of suspensions (and other short-term removals) when ensuring the provisions of FAPE” (DCL, 2016, p. 2).

This DCL indicated officials realized discipline and short-term removal of students with disabilities posed somewhat of a problem for school district administrators in 2016. The IDEA first addressed the discipline of eligible students with disabilities in 1997, and the law has not changed much since that time. There were a few changes in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, but rules regarding the discipline and short-term removals of students with disabilities for problem behaviors remain largely unchanged from the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Honig v. Doe (1988).

In late June 2022, officials at OSEP and at the Office of Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education believed issues in disciplining students with disabilities eligible under the IDEA and protected under Section 504 were unclear to many persons in school districts so both offices issued policy guidance statements on the topic.

The policy guidance issued by OSEP was a question and answer (Q&A) document. The document was divided into 10 areas:

- Obligations to meet the needs of eligible students with disabilities

- An overview of IDEA’s Discipline procedures

- Change in placement

- Interim alternative educational setting (IAES)

- Special circumstances

- Manifestation determination reviews

- IDEA’s requirements for FBAs and BIPs

- Provision of services during periods of removal

- Protections for students not yet determined eligible under the IDEA

- Application of IDEA Discipline protections in specific circumstances

- Resolving disagreements

- State oversight and data reporting responsibilities

In each of these topic areas, officials at OSEP posed between 3 and 12 questions and then provided their answers. The Q&A document also includes a glossary of key terms and acronyms used in the guidance. This is excellent policy guidance and should be read by officials, administrators, and teachers with concerns regarding the discipline of students with disabilities. The OSEP Q&A document can be found by clicking here. (https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/qa-addressing-the-needs-of-children-with-disabilities-and-idea-discipline-provisions.pdf).

The policy guidance issued by OCR was titled “Supporting Students with Disabilities and Avoiding the Discriminatory use of Student Discipline under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This policy document addressed FAPE issues, but primarily examined the discipline of students with disabilities from the standpoint of discrimination. It, too, is “must reading” for officials, administrators, and teachers with concerns regarding the discipline of students with disabilities. The OCR policy guidance can be found by clicking here. (https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/504-discipline-guidance.pdf).

Included behavioral programming in the IEPs of students with EBD is critical when necessary to provide a FAPE. It is also extremely important that any disciplinary procedures used with these students do not unilaterally change placement or deny them a FAPE. The three documents from OSEP and OCR are important policy guidance to ensure that students receive a FAPE and are disciplined using appropriate procedures.

Dear Miss Kitty: Advice Column

Dear Miss Kitty:

I was looking forward to returning to school next week to my class of middle schoolers with emotional/behavioral problems. I spent many hours in my classroom getting it all ready. Today I received a letter from the district central office stating I was being moved to a different school because they were short a teacher there. I called the office right away and neither the superintendent nor assistant superintendent would return my call. I then called the building principal of the school where I had been a teacher for ten years. The principal told me he couldn’t do anything about it, there was a shortage and the other teacher had quit so those students needed services more than the ones I was serving. When I asked the principal what would happen to my students, he said they were all being returned to general education full time. The movement was for inclusion in the district so in accord with that, the students would not receive special education. The social worker would help them in the transition. Is there anything I can do? I am overwhelmed at the thought of having one week to set up a class and am distressed at the thought that my previous students will receive no services, except for social work. What can I do?

Anxious Andrea

Dear Anxious Andrea:

I’m so sorry this is happening to you. With the shortage of teachers, some school districts are taking actions that may not be in the best interests of educators, families, and children. In their quest to solve an immediate problem, they are not always thinking of the major ramifications for the children and the hardship for educators. You should speak out on this because you have knowledge that your previous students are not going to be receiving their services. Here are some questions for you and some possible actions for you to take in protecting the children’s rights and your rights:

- Has the district convened new IEPS for the students that were in your class before? The administration cannot change the services without completing a new IEP for each student. There is no such thing as unilateral action in special education—the team decides, not the administrator alone. If there were new IEPS, then you need to find out who attended and send a letter to the administration voicing your concern that you were not involved. If no new IEPS were conducted, then you also need to write your concerns that services cannot be changed without new IEPS. Once you have put this in writing, you need to find out whether your state department of education has a complaint resolution process where you can file an anonymous complaint about what has happened. Otherwise, seek a good local advocate or an organization that advocates for students with special needs. You have knowledge the district may have violated the children’s rights and you need to take action to inform. You should also reach out to the school social worker to see if he or she is aware of what is happening.

- You have a contract with your district and yours would be a continuing one. You need to review that contract and see what it allows in terms of changing your position with short notice, some districts are doing this, sad to say, but examine what you agreed to in your contract. You also may belong to your teacher representative organization, and they have a contract between the teachers and the district. Notify that representative and see whether there is anything they can do to assist you and I hope they can. You may also want to seek out your other professional organizations like this one to see if there is anything they can do to assist you.

- Do what you can to get the new room ready—those new students need you – but recognize you won’t be able to do as much as you had done to get ready for what should have been your returning class. Use this time for some internal searching about whether you wish to remain in this district where such practices take place. You may want to begin thinking about a change in districts for the next school year, but you want to make the effort to see the students you were supposed to have get their needs met and that you find out what recourse you have when your position was changed with such short notice.

I wish you the best and thank you for the concerns you have for your students.

Early Adopter or Laggard: What to do with teacher TikTok

Abbi Long

Maybe it is futile, but the education futurist in me believes even more change is on the horizon for public education and teacher education. For some, change is hard. For most, change takes time. Indeed, many educators enter the field motivated by the desire to bring about change. Many enter teacher education for students with emotional and behavioral needs with similar hopes to change the systems, structures, and policies that impact the students, their families, and their teachers. Social media is a platform of innovation and change.

As an “elder millennial” I did not grow up with social media. I did embrace social media early on with one exception, TikTok. Though TikTok emerged on the scene in 2016, I only downloaded the app about one year ago. According to the social media platform’s website, “TikTok is the leading destination for short-form mobile video. Our mission is to inspire creativity and bring joy.” Their mission may seem simple, but it does bring many people joy. Short videos of dogs, carpet cleaning, power washing, and food require no deep thinking or energy. These short, captivating videos can also be used as a quick way to share useful information to a wide audience. Like many other social media platforms, TikTok uses an algorithm to tailor what videos show up on a user's “For You” page based on searches and engagement with hashtags. In other words, if future and current teachers search or engage with hashtags related to education like #teachertiktok #teachersontiktok #tiktokteacher, they are more likely to encounter future videos of the same kind.

While social media such as TikTok makes many roll their eyes and resist change, other now mainstream innovations such as cell phones, online meetings, and even virtual learning faced similar resistance as well early on. This leads us to the diffusion of innovations theory originated by E. M. Rogers (2003). The diffusion of innovations theory is composed of different types of attitudes regarding new ideas (the innovator, the early adopter, the early majority, the late majority, laggards). The creators of TikTok are likely considered innovators. When many adults aged 18 to 34 joined TikTok, they became early adopters. While the late majority and laggards may feel tired of virtual interactions, early adopters of TikTok are seizing the opportunity and engaging with people in joyful and creative ways, especially on #teachertiktok. Early adopters of TikTok have built an entire community uninhibited by physical location where ideas, humor, and practices are spread.

Although it may be too late to be an early adopter, it is not too late to join the early majority. Therefore, I issue this challenge: Embrace TikTok. Connect with current and future teachers. Create and share evidence-based practices in short, meaningful segments. Many undergraduate students grew up engaging with TikTok. Many young professionals are still using the app. Imagine using TikTok to explain how to use behavior specific praise or instructional choice. What would it be like to create short videos on time sampling procedures for behavior monitoring? Undergraduate and graduate students could even create this kind of content as part of an assignment. Finally, consider engaging with others’ content in cathartic ways, releasing negative energy, and laughing at this amazing field we all love.

Consider these fun videos I found as a starting place:

- Teacher Professional Development

- Back to School

- Do we need filing cabinets?

- Covering for Kindergarten

Above all else, avoid being a laggard. If after years of interacting with each other in the virtual sphere you have not found your way to TikTok, maybe it is not too late. I will see you there.

References

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. (5th ed.) The Free Press.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions for ADHD & Emotional-Dysregulation in the Classroom

Megan A. McBride

Department of Educational Instruction and Leadership, Southeastern Oklahoma State University

Dr. Kathleen Boothe

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common developmental disorder that falls within the neurodivergent developmental disorder group, which includes disorders like autism and dyslexia (Stenning & Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist, 2021). The largest deficit for emotional development in adolescents who have ADHD is the inability, or difficulty, to regulate emotion. The ability to self-regulate is crucial to develop emotional regulation. If an adolescent is not able to regulate her emotions, she may suffer from emotional dysregulation. Emotional dysregulation is the inability to process and/or communicate feelings in a positive and productive way (Bunford et al., 2015). Addressing cognitive function deficits and emotional dysregulation can be extremely challenging for educators. Utilizing mindfulness-based interventions creates a positive learning environment for all students while allowing students with ADHD to flourish academically and emotionally in the classroom.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Students with ADHD and emotional dysregulation often struggle with rumination and may become overstimulated when not meeting expectations regarding academics. As students have racing thoughts, they may become overstimulated and either have an emotional episode or emotionally shut down (Hatak et al., 2021). While this is an emotional response, it directly affects the student’s overall academic ability. To assist students coping with inattention and emotional reactions, educators can utilize mindfulness-based techniques that focus on enhancing executive functions.

Self-Talk Procedures

Self-talk procedures is a mindfulness-based intervention that allows individuals to understand their own thought processes while enhancing executive functions (Broderick & Blewitt, 2020). Self-talk procedures involve enhancing procedural and conceptual knowledge for students to gain better studying habits and enhance their logical problem-solving abilities, which is beneficial to academic studies and interpersonal relationships (Broderick & Blewitt, 2020).

Self-talk procedures include (Sethi, 2021):

- Analyzing and Understanding One’s Own Thoughts

- Acknowledging Negative Thoughts About One’s Self

- Using Positive Affirmations

This technique also gives students tools to reinvent their language regarding negative conceptions about themselves. For example, instead of saying “I’m bad at math,” students will be taught to rethink their stance regarding their math abilities by saying “I failed the math quiz because I did not study the steps beforehand.” Statements like this improve self-confidence while allowing an “I can’t” mindset to shift to “I can, and I need to study in a more meaningful way” mindset, which is beneficial for students with ADHD (Broderick & Blewitt, 2020).

Guided Meditation

Guided meditation involves a guide instructing a student, or group of students, in breathing exercises, mental imagery, and various calming techniques (Morin, 2020). Meditation teaches students how to take an observational approach to a situation while understanding negative emotional states are temporary, which reduces stress and reactive responses (Bachmann et al., 2016).

According to Bachmann et al. (2016), guided meditation is beneficial to students who:

- Ruminate

- Daydream

- Exhibit impulsiveness

- Easily distracted while doing daily tasks

Meditation is a skill that can be taught and enhanced over time. Practicing the act of meditation will allow students who struggle with emotional dysregulation become more aware of their emotions and will be better equipped to manage their emotional reactions.

Memory Enhancement Coaching

Memory enhancement coaching provides students with tools and strategies that will enhance their working memory and academic abilities (Dehn, 2011).

Memory enhancement coaching includes teaching students how to:

- Set Reminders for Important Events

- Use a Calendar and/or Planner

- Chunk Pieces of Information Together (“Chunking”)

- Use Active Recall Strategies

- Create Mnemonics

Setting reminders and using calendars/planners are specifically helpful to students suffering from ADHD and issues regarding working memory (Dehn, 2011). Chunking, piecing together bits of information to create a total unit of information, enhances overall academic abilities (Broderick & Blewitt, 2020). Active recall strategies have proven to be more effective in long-term memorization than regular studying habits (Xi et al., 2020). A common and effective active recall strategy is using flashcards.

Mnemonics improve cognitive abilities by using self-generated cues, which are more effective than cues generated by others because students can use cues that are custom to their specific memory needs (Tullis & Fraundorf, 2022). An example of a common mnemonic for memorizing cardinal directions (North, South, East, West) is: (N)ever, (E)at, (S)our, (W)atermelon.

Making Mindfulness a Priority in the Classroom

While in the classroom, it is always expected to focus on academics first. However, emotional dysregulation can be extremely difficult for adolescents to cope with. Many adolescents may not realize why they are doing poorly in certain subjects while excelling at others. It is a common misconception that academics, social skills, and emotions are dependent attributes in education. However, all three attributes are interdependent and need each other to thrive. Emphasizing mindfulness-based strategies in the classroom can significantly help students with ADHD and emotional-dysregulation improve their academic success and emotional intelligence.

References

Bachmann, K., Lam, A. P., & Philipsen, A. (2016). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and the adult ADHD brain: A neuropsychotherapeutic perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7(117), 1-7.

Broderick, P., & Blewitt, P. (2020). The life span: Human development for helping professionals (5th ed.). Pearson.

Bunford, N., Evans. S. W., & Wymbs, F. (2015). ADHD and emotion dysregulation among children and adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(3), 185–217.

Dehn, M. J. (2011). Helping students remember: Exercises and strategies to strengthen memory. Wiley.

Folquitto, C. T. F., Rodrigues, C. L., Andrade, E. R., Rocca, C. C., & Souza, M. T. C. C. (2014). Considerations about psychological development of children with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). Psychology Research, 4(3), 168-177.

Hatak, I., Chang, M., Harms, R., & Wiklund, J. (2021). ADHD symptoms, entrepreneurial passion, and entrepreneurial performance. Small Business Economics, 57(4), 1693-1713.

Morin, A. (2020). The simplest way to begin a guided meditation. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/guided-meditation-getting-started-4174283

Sethi, B. (2021). Using positive self-talk to improve your kid’s mindset and behavior. FirstCry Parenting. https://parenting.firstcry.com/articles/using-positive-self-talk-to-improve-your-kids-mindset-and-behavior/

Stenning, A., & Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist, H. (2021). Neurodiversity studies: Mapping out possibilities of a new critical paradigm. Disability & Society, 36(9), 1532-1537.

Theodor-Katz, N., Somner, E., Hesseg, R.M., & Soffer-Dudek, N. (2022). Could immersive daydreaming underlie a deficit in attention? The prevalence and characteristics of maladaptive daydreaming in individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1-20.

Tullis, J. G., & Fraundorf, S. H. (2022). Selecting effectively contributes to the mnemonic benefits of self-generated cues. Memory & Cognition, 50(4), 765-781.

Xi J., Chuanji G., Lixia C., & Chunyan G. (2020). Neurophysiological evidence for the retrieval practice effect under emotional context. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 147, 224-231.

“I Got that Summertime, Summertime Response Effort”

Eric Alan Common, Ph.D., BCBA-D, University of Michigan-Flint

Recreational Reinforcement is a column highlighting the recreational and leisurely pursuits of educators and professionals while also making connections and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. This month’s column introduces response effort as a behavior change tactic (e.g., independent variable) to increase or decrease target behaviors with attention to recreationally and leisurely pursuits in summertime.

Keywords: response effort, behavior change, summer

2022-2023 Call for Columns:

Recreational Reinforcement is a bi-monthly (6/year) column dedicated to discussing recreational or leisurely pursuits, making connections, and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. The only rule is nobody wants to hear about work being your “recreational reinforcement.” Please send submissions or inquiries to Dr. Eric Common at [email protected]. Directions for submissions: (a) article title, (b) names of author(s), (c) author’s affiliations, (d) email address, and (e) 700–1500-word manuscript in Times New Roman font. Bitmoji, graphics, tables, and figures are optional.

“I Got that Summertime, Summertime Response Effort”

Have you ever noticed even though you like a variety of things you or more likely to engage in some preferred leisure activity over other leisurely activity just as preferable? Or that you tend to engage in the same leisure activity time and again, even though you have a wide range of leisurely activities you enjoy. If so, you are not alone and while there could be several reasons for this one might be the response effort required to engage in some leisurely activities over others.

Response Effort

Response effort, like it sounds, refers to the actionable efforts required to engage in a response (Wilder et al., 2020). In basic and applied research, the distance, force, or number of discrete actions have all been manipulated as an index of response effort—and thus manipulated as an independent variable. Research in manipulating response effort suggest participants generally, prefer low effort responding over high effort responding, response rate decreases as effort increase, and escape behaviors are more likely in situations requiring particularly effortful responding (Friman & Poling, 1995; Wilder et al., 2020).

Collectively, these findings suggest response effort can serve as a powerful behavior change tactic by adjusting the environment and thus increasing or decreasing the response rate, like procedures employing reinforcement or punishment-based procedures (Friman & Poling, 1995).

Leisurely Walks

Walking is a preferred activity of mine, I enjoy walking in my neighborhood, urban, rural, and wilderness areas alike. That said, some walks are better than other. Like many things in life, the best walks tend to have a little bit more response effort. Without much thought, I can think of a route in my neighborhood to meet any time constraint. Similarly, I can think of paved trails and hiking trails within my city, county, and within an hour drive. Some trails I walk on regularly, others have been on my wish lists for years, and others I appreciate just knowing they, and others I don’t even know about, are out there. I value and am committed to walking and exploring but I am often more likely to do the familiar.

One strategy to increase the probability I will hit a trail I really love or try something new is to decrease the response effort. For me this includes being prepared and having the time. Examples of preparedness might include knowing the route and commute time, having my water bottle, and any bug repellent as necessary. With regards to time, I can decrease the response effort by having walking and traveling be part of my regular schedule and routine.

Final Thoughts

For DEBH professionals, family, and community members, as well as helping professionals in general, it can be challenging to having work-life balance. For some of us—myself in particular—some behavior-change tactics have more or less social validity. For example, I am more likely to successfully shape my behavior with antecedent-based adjustments than consequence-based continencies. When it comes to my weekend, I do not want to engage in behavior change tactics in play – but I may want to adjust my behavior. Response effort offers another powerful tool at my disposal to effect positive behavior change.

References

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis. Pearson.

Friman, P. C., & Poling, A. (1995). Making life easier with effort: Basic findings and applied research on response effort. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(4), 583-590. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1995.28-583

Wilder, D. A., Ertel, H. M., & Cymbal, D. J. (2021). A review of recent research on the manipulation of response effort in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Modification, 45(5), 740-768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445520908509

Author Bio

Eric Common is an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan-Flint in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral Level. He is leads Recreational Reinforcement with Erin Farrell and Co-Chair’s DEBH’s Professional Development Committee.

Family Matters: How to Support Teachers of Students with EBD

Justin Garwood

Burnout of special educators serving students with and at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) is often attributed to challenges supporting student behavioral needs (Garwood et al., 2018; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017), as well as hostile working conditions (e.g., lack of administrative support; Bettini et al., 2020). As a result, teachers of students with EBD have some of the shortest teaching careers (Prather-Jones, 2011). For teachers who stay in the field, those rating higher on burnout produce lower quality individualized education programs (IEPS) for their students (Ruble & McGrew, 2013) and their students achieve IEP goals less often (Wong et al. 2017). What is more, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused irreparable harm and interruption to students’ educational development (Hirsch et al., 2021; Kim & Fienup, 2021), which can logically be assumed to only increase the number of students at risk for EBD and the need for special educators who can address their needs (Lund et al., 2020). Public schools provide most mental health services to students in need (LoCurto et al., 2021); however, despite decades of intervention research, outcomes for these students remain disconcerting (e.g., low academic performance, dropout, criminal arrest; Garwood et al., 2020; U.S. Department of Education, 2018; Wagner, 2014).

It is increasingly clear teachers alone cannot properly meet the needs of students with and at risk for EBD: there is a pressing need for interagency collaboration (Bixler & Anderson, 2017; Cornell & Sayman, 2020) and family partnership (Turnbull et al., 2022). Recent literature indicates 30-50% of children with EBD have experienced trauma and/or adversity, suggesting a need for a trauma-sensitive approach in addition to other positive behavior interventions (Hurless & Kong, 2021; Mueser & Taub, 2008). Ensuring teachers, special educators, social workers, other educational professionals, and families effectively collaborate, and are skilled in trauma-sensitive approaches (e.g., encouraging dignity, respect, and compassion), is essential for maximizing the psychological safety necessary for learning, development, and educational well-being (Strolin-Goltzman, 2014).

Models such as Systems of Care (Stroul et al., 2010), school-based mental health centers, and Full-Service Community Schools (Min et al., 2018) are examples of collaborative approaches, which involve professionals from different agencies working together to support families and students (Cooper et al., 2016). The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provides a clear legislative mandate for collaboration among teachers, students, families, and communities to best meet the needs of students at risk for school failure, such as those with and at risk for EBD. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for increased family and community partnership, and the American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief specifically requires that SEAs and LEAs submit a plan for strengthening family and community partnership (U.S. Department of Education, 2021).

There must be an intentional effort to create the conditions in inclusive schools most likely to keep highly qualified teachers of students with EBD in the field. Teachers regularly cite the support they receive from their administrator(s) as more important than their salary regarding their decision to stay in or leave the profession (Brown & Wynn, 2009). Strong administrative support facilitates inclusive instruction and proactive family partnerships (Francis et al., 2015; Turnbull et al., 2022). Family, school, and community collaboration is a powerful way in which the responsibility for meeting the mental health needs of students with and at risk for EBD can be shared and coordinated instead of falling solely to special educators (He et al., 2018; Turnbull et al., 2022).

References

Bettini, E., Cumming, M., O’Brien, K. M., Brunsting, N. C., Ragunanthan, M., Sutton, R., & Chopra, A. (2020). Predicting special educators' intent to continue teaching students with emotional/behavioral disorders in self-contained classes. Exceptional Children, 86, 209-228.

Bixler, K., & Anderson, J. A. (2017). Interagency collaboration to improve school outcomes for students with mental health challenges. Global Ideologies Surrounding Children’s Rights and Social Justice, 140-155.

Brown, K. M., & Wynn, S. R. (2009). Finding, supporting, and keeping: The role of the principal in teacher retention issues. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8, 37-63.

Cooper, M., Evans, Y., & Pybis, J. (2016). Interagency collaboration in children and young people’s mental health: A systematic review of outcomes, facilitating factors and inhibiting factors. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(3), 325-342.

Cornell, H. R., & Sayman, D. M. (2020). An exploratory study of teachers’ experience with interagency collaboration for the education of students with EBD. Preventing School Failure, 64(2). 155-161.

Francis, G. L., Kilpatrick, A., Haines, S. J., Gershwin, T., Hossain, I., & Kyzar, K. (2021). Family-professional partnerships in special education teacher preparation: Uncovering the what, why, and how. Teaching and Teacher Education. Accepted for publication.

Garwood, J. D., Peltier, C., Sinclair, T., Eisel, H., McKenna, J. W., & Vannest, K. J. (2020). A quantitative synthesis of intervention research published in flagship EBD journals: 2010-2019. Behavioral Disorders. Advanced online publication.

Garwood, J. D., Werts, M. G., Varghese, C., & Gosey, L. (2018). Mixed-methods analysis of rural special educators’ role stressors, behavior management, and burnout. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37, 30-43.

He, A. S., Phillips, J. D., Lizano, E. L., Rienks, S., & Leake, R. (2018). Examining internal and external job resources in child welfare: Protecting against caseworker burnout. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 48-59.

Hirsch, S. E., Bruhn, A. L., McDaniel, S., & Mathews, H. M. (2021). A survey of educators serving students with emotional and behavioral disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic. Behavioral Disorders. Advanced online publication.

Hurless, N., & Kong, N. Y. (2021). Trauma-informed strategies for culturally diverse students diagnosed with emotional and behavioral disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic. Advanced online publication.

Kim, J. K., & Fienup, D. M. (2021). Increasing access to online learning for students with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Special Education. Advanced online publication.

LoCurto, J., Pella, J., Chan, G., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2021). Caregiver report of the utilization of school-based services and supports among clinically anxious youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 29(2), 93-104.

Min, M., Anderson, J.A., & Chen, M. (2018). What do we know about full-service community schools? Integrative research review with NVivo. School Community Journal, 27(1), 29–54.

Mueser, K. T., & Taub, J. (2008). Trauma and PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional disorders involved in multiple service systems. Psychiatric Services, 59(6), 627-634.

Prather-Jones, B. (2011). “Some people aren’t cut out for it”: The role of personality factors in the careers of teachers of students with EBD. Remedial & Special Education, 32, 179- 191.

Ruble, L. A., & McGrew, J. H. (2013). Teacher and child predictors of achieving IEP goals of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2748-2763.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611-625.

Strolin-Goltzman, J., Breslend, N., Deaver, A. H., Wood, V., Woodside-Jeron, H., & Krompf, A. (2020). Moving beyond self-care: Exploring the protective influence of interprofessional collaboration, leadership, and competency on secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology. Advance online publication.

Stroul, B., Blau, G., & Friedman, R. (2010). Updating the system of care concept and philosophy. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health.

Turnbull, A., Turnbull, R., Francis, G. L., Burke, M., Kyzar, K., Haines, S. J., Gershwin, T., Shepherd, K. G., Holdren, N., & Singer, G. (2022). Families and professionals: Trusting partnerships in general and special education. Pearson.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs. (2018). 39th annual report to congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2017.

U.S. Department of Education. (2021, April 21). State plan for the American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. Retrieved from: https://oese.ed.gov/files/2021/04/ARP-ESSER-State-Plan-Template-04-20-2021_130PM.pdf

Wagner, M. (2014). Longitudinal outcomes and post-high school status of students with emotional or behavioral disorders. In H. Walker & F. Gresham (Eds.), Handbook of evidence-based practices for emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 86-103). Guilford.

Wong, V. W., Ruble, L. A., Yu, Y., & McGrew, J. H. (2017). Too stressed to teach? Teaching quality, student engagement, and IEP outcomes. Exceptional Children, 83, 412-427.