Behavior Today Newsletter 41.4

DEBH Call for Nominations: Open now through January 19, 2024

DEBH is calling for nominations for four open Executive Committee positions and one elected committee position to begin July 01, 2024. Full descriptions of each office are available on the DEBH website and more information can be obtained by contacting the DEBH Past President (Tim Landrum; [email protected]) or the Nominations and Elections Committee ([email protected])

Vice President – 1-year term (2024-2025)

The Vice President is an important role in shaping the vision and mission of the organization, as well as supporting member-related activities. The elected person will serve one year before ascending to President Elect, President, and then Past President over 4 consecutive years.

Representative to the CEC Representative Assembly (Representative “A”) – 2-year term (2024-2025, 2025-2026)

Representatives to the CEC Representative Assembly provide a crucial link between DEBH and the larger CEC organization, acting as a liaison between the DEBH Executive Committee, DEBH Regional and State Membership, and CEC.

International Member-at-Large – 2-year term (2024-2025, 2025-2026)

The International Member-at-large (MAL) works with the DEBH Executive Committee to expand the perspective of DEBH outside of the United States.

Inclusion, Equity, and Diversity Member-at-Large – 2-year term (2024-2025, 2025-2026)

The Inclusion, Equity, and Diversity Member-at-large (MAL) establishes and maintains a communication network to ensure that persons of diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds have an active voice in DEBH activities and decision-making.

Nominations and Elections Committee Member – 3-year term (2024-2025, 2025-2026, 2026-2027)

The Elections and Nominations committee members work with the Past President to conduct elections according to the DEBH Constitution and By-Laws.

Nomination and Submission Instructions

Nominators must send a signed letter to the DEBH Nominations and Elections Chair, Tim Landrum. This letter must include the nominator's DEBH membership number to validate DEBH membership of the nominator.

DEBH Past President

Tim Landrum

Nominations and Elections Committee

Rebecca Sherod

Mary Rose Sallese

Heather Griller Clark

Individuals nominated by another party must affirm their agreement by a separate letter to the Nominations and Elections Committee Chairperson, and must include the following materials:

- Statement from nominee, separate from the nominator’s letter, agreeing to be nominated.

- CEC membership number of the nominee, to validate DEBH membership.

- Three-part statement that presents, in 1,000 words or fewer, the following:

- issue(s) relevant for the Division for Emotional and Behavioral Health (may involve students, professionals, or other issues);

- proposed responses needed to deal with issue(s) identified; and

- how the nominee, if elected, can work on the DEBH Executive Committee in responding to these issue(s).

- Condensed resume or vita (maximum of three pages).

- A ballot statement describing nominee’s qualifications, perspectives, and/or goals. This will be included in the ballot verbatim, and length must not exceed 100 words.

- A photograph (ideally professional headshot) to be used on the ballot and DEBH social media (website, Facebook, Twitter, Behavior Today newsletter, etc.) Submitting the photograph serves as permission to use the photo in DEBH media.

The deadline for nominations and all supporting material for offices is January 19, 2024, and the election period will begin no later than February 1, 2024 and end no sooner than March 4, 2024.

My Most Memorable Student: Voices from the Field – Frank Wood

Jim Teagarden & Robert Zabel, Kansas State University

The Janus Oral History Project collects and shares stories from leaders in education of children with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). The Project is named after the Roman god, Janus, whose two faces look simultaneously to the past and future.

One Janus Project activity is recording and sharing educators’ descriptions of memorable students. They are asked: Who is your most memorable student? What did you learn from this student? How has the student impacted your career or life? What follows is Dr. Frank H. Wood’s story of Mike.

* * * * *

“The student who made the biggest impact on me was in 1958. I was teaching in a regular 5th grade classroom in Minneapolis. The state had just passed a law that permitted, not required, schools to set up classrooms for students who were socially maladjusted. They would reimburse part of the teacher’s salary who would teach such a class. I had a boy in my class, Mike. I can’t tell you all the adventures we had, but one I remember was during the winter in the snow. It involved Mike and a 6th grade boy who was in the school safety patrol.

The safety patrol guy was very flushed and upset. He said Mike was walking in the street, and he told him he couldn’t do that. “Mike then threw snowballs at me, and I told him he couldn’t do that. Then Mike pushed me in the snow and put snow down my coat.” Mike was standing there as the boy told his story. I told the school safety patrol, “I’ll take care of it.”

When I asked Mike, “What happened?” he replied, “I went home for lunch, and nobody was there.” One of the things I learned from Mike that year was some of the situations which overwhelmed him as he was trying to cope with while being neurologically immature.

The state had passed this new law and there was a notice about it in the school newsletter. They announced they were going to set up a class for students who were socially maladjusted or emotionally disturbed in the fall. I thought Mike would really benefit from this since my class had 42 students. So, I called and suggested they think of Mike as a possible candidate for the new class. They called me back because, apparently, I was the only teacher that had called the special education office. They asked my principal about me and then called me to see if I would teach this class. The next fall we did start the special class—the first class for students with emotional disturbance in Minnesota within a regular school.

I learned several things from the students I had in my class. One of them was about coping. You had to understand the students were often coping with the terrible environments they were living in or in some cases brain trauma due to injury or disease. The special classroom represented a safe place for some.

One of the highlights was sitting around a table each morning we sat around and passing out two saltine crackers to each student. The behavioral approach was just being developed, but one of the things I learned was that if a student was out of line prior to the cracker break, I’d say “Okay, only one cracker.” You never said, “No crackers.” We would eat the crackers together and have a nice conversation in the group. The crumbs would fall on the paper towel, and the students would suck up the crumbs.

It was during one of these “cracker breaks” that a student put his arm around me and said, “You know, Mr. Wood, this is the greatest class I’ve ever been in.” That kind of breaks your heart. You wonder what kind of experience he has been having. These students teach you lots of things but one of them is what they are coping with. They need a lot of support, they need guidance, but most of all they need some kindness.”

* * * * *

It is with heavy heart that the Janus Project shares the loss of Dr. Wood on Dec. 11, 2023. Frank was a gentle giant, a pioneer of our field. He was a teacher, advisor, leader, model, and friend. Among his many contributions was leadership of the Advanced Training Institute (ATI) at the University of Minnesota in the 1970s and 1980s. The ATI brought together pioneers and first-generation educators of students with EBD to generate and share ideas, expertise, research, and mutual support.

Frank served in many professional leadership roles, including President of The Council for Children with Behavior Disorders (now, Division of Emotional and Behavioral Health), and two terms as Editor of Behavior Disorders.

Frank’s story about his student, Mike, is a part of the Midwest Symposium for Leadership in Behavior Disorders video series, “My Most Memorable Student.” It is available for viewing at: Frank Wood's story. More than 40 stories of memorable students can be seen at: http://mslbd.org/what-we-do/educator-stories.html.

Also, a video recording of Dr. Wood’s Janus Project interview can be viewed at MSLBD.org., and it is also available in print (Zabel et al., 2011), as is a conversation with Frank published in ReThinking Behavior (Teagarden et al., 2017).

References

Teagarden, J., Zabel, R. H., & Kaff, M. S. (2017). A conversation with Frank Wood, ReThinking Behavior, 1(1), 3-6. (MSLBD.org)

Zabel, R. H., Kaff, M. S., & Teagarden, J. M. (2011). Understanding and teaching students with emotional/behavioral disorders: A conversation with Frank H. Wood, Intervention in School and Clinic, 47(2), 125-132.

“Monitoring New Year’s Resolutions”

Eric Alan Common, Ph.D., BCBA-D, University of Michigan-Flint

Erin Fitzgerald Farrell, Ed.D., BCBA, University of St. Thomas

Recreational Reinforcement is a column highlighting educators' and professionals' recreational and leisurely pursuits while making connections and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. This month’s column explores measuring and monitoring New Year’s Resolution Goals. When one is behaviorally informed, they have a unique opportunity to apply an understanding of behavior to their own lives. This New Year, let's approach our resolutions not just with hope but with acceptable, reliable, and valid behavior measurement systems to collect, graph, and visually inspect behavior changes with visual analysis.

Behavior Measurement Stems

Behavior has multiple dimensions, each offering unique insights. These dimensions include repeatability (behavior can occur repeatedly; can be counted), temporal extent (behavior occurs during some amount of time), and locus (behavior occurs somewhere in time and space). By identifying the specific dimension of behavior, we wish to change, we can tailor our approach and measure progress effectively. Selecting an appropriate measurement system that aligns with the behavior dimension you wish to change is essential. Here are some key measurement systems and their considerations:

| Measurement System | Definition | Some Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Recording | Counts the number of times a behavior occurs. | Useful for behaviors consistent in duration and form (i.e., uniform behaviors). |

| Rate Recording | Calculates a ratio of behavior count per observation time. | Relevant for quantifying frequency over time, such as in time-bound tasks or to standardized variable observation lengths. |

| Duration Recording | Measures how long a behavior lasts. | Ideal for behaviors that last long or short amounts of time. |

| Latency Recording | Records the time between a given stimulus and the start of a behavior. | Helpful to assess response times to stimuli. |

| Topography Recording | Assesses the physical form and structure of a behavior. | Useful for qualitative assessment of behaviors like writing or physical or holistic skills. |

| Locus Recording | Focuses on the location or context where a behavior occurs. | Important for understanding behavior in different environmental contexts. |

| Force Recording | Evaluates the intensity or strength of a behavior. | Applicable when analyzing the severity or mildness of behaviors. |

| Partial Interval Recording | Behavior is recorded if it occurs at any time during the interval. | Tends to underestimate or overestimate behavior. |

| Whole Interval Recording | Behavior is recorded if it occurs throughout the entire interval. | Tends to underestimate behavior; suitable for behaviors to increase. |

| Momentary Time Sampling | Observes whether the behavior is occurring at specific moments. | Flexible; provides a snapshot of behavior at specific intervals. |

| Trials to Criterion Recording | Records the number of attempts a subject takes to meet a predetermined level of performance or mastery. | Allows for the measurement of learning rate and efficiency. |

| Discrete Trial Recording | Documents each individual opportunity or trial presented to a subject, along with their response. | Enables detailed analysis of both correct and incorrect responses; useful for tracking progress on specific skills in a controlled, structured manner. |

By choosing a measurement system aligned with one’s resolution's behavioral dimension can more accurately track and understand one’s progress.

Visual Analysis

By graphically displaying data collected through various behavior measurement systems, visual analysis allows for an immediate and nuanced understanding of change over time. This process involves graphically representing your collected data to identify patterns, trends, and the overall effectiveness of your behavioral change strategies. Ideally, graphic data are organized by phases. This might include baseline (A) and Intervention (B). In the case of a new year’s resolution, the baseline would be before the start of the new year’s resolution. Various single-case research designs use various condition configurations (e.g., A-B-A-B) to evaluate the effects of behavior change programs. Here's a brief overview of key components of visual analysis and some considerations:

| Visual Analysis | Definition | Some Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Level | The average value of the data within a phase indicates the overall performance. | Determine desired performance (level). Look for changes in level within and across phases (e.g., baseline, resolution, intervention). Consider the baseline level as a comparison for intervention effects. |

| Trend | The direction and rate of change in data across time, indicating an increasing or decreasing pattern. | Determine desired direction (trend; increasing, decreasing, or zero trend) of behavior change. Look for changes in trend within and across phases. Evaluate the consistency of the trend within and across phases. |

| Stability | The extent to which data points fluctuate around the level or trend line indicates the data's consistency. | Assess variability in data points around level and the trend. Look for changes in stability within and across phases. Consider predictability of behavior. |

By monitoring one’s behavior change across level, trend, and stability, one can assess progress, make informed decisions, and adjust strategies for better outcomes.

As we step into the New Year, let's not only be hopeful but also strategic and analytical in our approach to behavior change. Here's to a year of meaningful transformation and success in all our endeavors. Wishing everyone a safe, productive, restful, and joyous New Year, filled with insightful discoveries and rewarding achievements.

Authors Bio

Eric Common is an Associate Professor at the University of Michigan-Flint in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral Level.

Erin Fitzgerald Farrell is an Adjunct Professor at the University of St. Thomas in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst.

Let’s Make a Deal: The Combined use of the Premack Principle and Visual Supports to Motivate Students and Increase Appropriate Behavior

Doris Hill and J. T. Taylor

First/then boards, token economies, Daily Behavior Report Cards (DBRC), and contingency contracting are all designed to motivate student performance. Their use is not new. They can be used in classrooms, clinics, residential facilities and can be used in conjunction with each other. They have been used for individuals with disparate challenges, with and without disabilities. Rousseau (1971) described the use of these interventions in a re-education school for children with emotional disturbance. They have been used in schools with students with and without Individual Education Programs (IEPs). The teacher/clinician will conduct a preference assessment utilizing one of several strategies. Multiple stimulus without replacement (SMWO), multiple stimulus with replacement (MSW), free operant observations- roaming in a classroom with toys laid out, or just asking the student what they want to work for. These interventions are relatively simple to implement. Once a target behavior has been identified these strategies can help not only reduce problem behaviors, but also increase engagement. These interventions utilize visual methods to help students understand your expectations, complete a task, and earn a reward.

The interventions mentioned above are the Premack Principle, which states that any Response A can reinforce any other Response B. This theory demonstrates reinforcer relativity, where the relative probabilities of responses can be more impactful when preference is incorporated (Herrod et al, 2023).

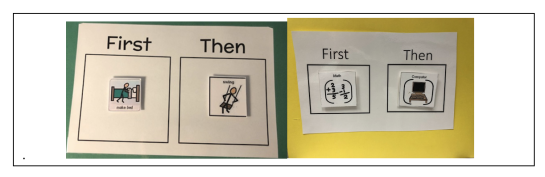

First/then boards. First/then boards are based on the Premack Principle or “grandma’s law” (“first you eat your broccoli, then you can have ice cream;” Cooper et al., 2020). First/then boards communicate an expected task which, upon completion, will be followed by a more preferrable activity. For example, first the student must complete mathematics problems, and then the student can have a break or read their favorite book. Making a first-then board can be as simple as dividing a sheet of blank paper into two parts. Label the left side, FIRST, and the right side, THEN. Attach a picture or photograph of the activities. The pictures below show example of visuals used to communicate expectations in which students first work, complete a center, or make their bed and then they can engage in a preferred activity of circle time, using a swing, or packing up to go home.

Figure 1. Example of a sign and first-then boards.

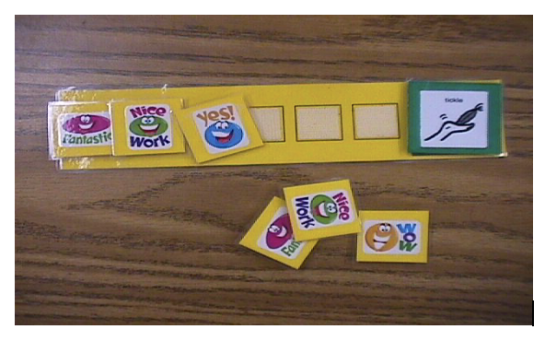

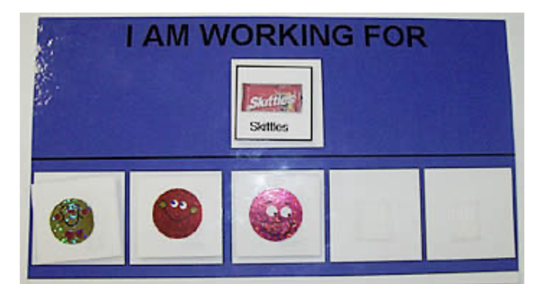

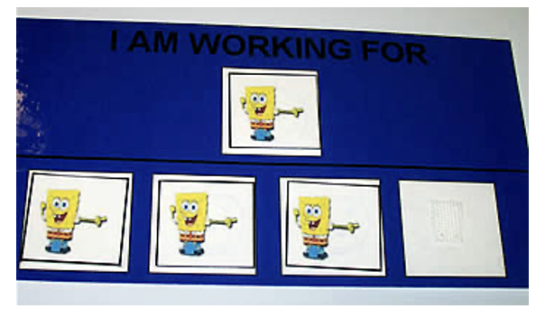

Token Economies. Token economies extend the expectation to complete a task which can be turned in for the earned reward (preferred item or activity). The tokens themselves are sturdy symbolic representations. Token economies can be used with an individual student or to larger groups. Each student can earn tokens which can be turned in for a preferred item based on each student’s preferences. Unlike edibles, tokens are seldom subject to satiation. Tokens can be dispensed without interruptions of instructional time.

There are two components to the token economy: the tokens themselves and the back-up reinforcers. The tokens have no value in themselves, not easily counterfeited, are durable, convenient to dispense, and can take any number of forms.

Figure 2. Example of token economies.

The back-up reinforcers are items “purchased” with the accumulated tokens. For groups, a variety of items are made available to members of the group. Some teachers will design their own “bucks” which can be traded at the end of the week or saved for bigger items offered at a higher “price. “Many retail venues use token economies. Think of cards used by ice cream shops and some retail outlets. When you buy an ice cream, they stamp your card. When you fill the card, you can earn a free ice cream.

The general rules for setting up a token economy include identifying target behaviors that will earn tokens, creating the tokens, identifying back-up reinforcers and the frequency of being dispersed, and determining how many tokens can be earned in one day. For individual token economies, determine how many tokens they need to earn to access the reinforcer. The token is “earned” when the student is engaging in the behavior you want to see.

Behavior Contracts. Behavior contracts can be used across settings or subjects during the school day. They are worded positively, individualized, and include active participation by the student. They are an extension of the principles utilized in the first/then contingency and the token economy (Taylor & Hill, 2017).

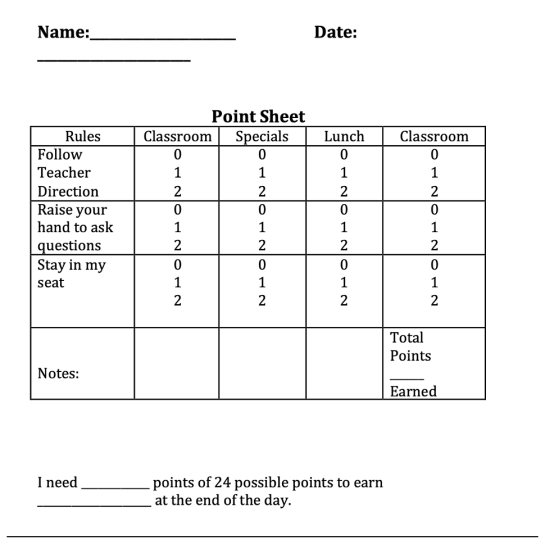

They can be a behavior specific contract that the student carries to each class or subject if the student does not take change classes. If used in the classroom, the teacher goes over the point sheet at the end of each activity listed on the DBRC. If used across the school day, the student checks in with an adult and checks out with the teacher at the end of the day to access the reward if they meet their goal.

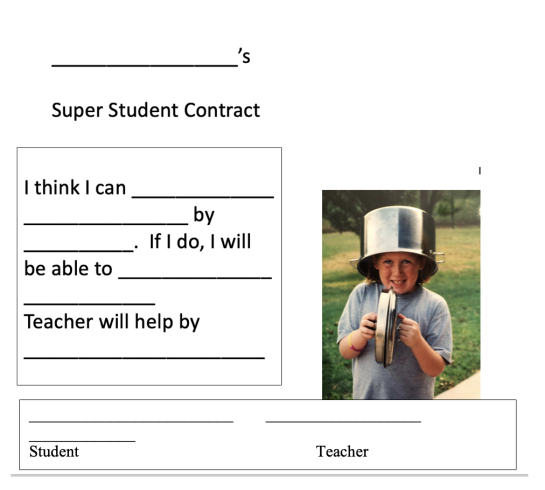

Figure 3. Example of contingency contracting

Figure 4. Example of contingency contracting

Behavior contracts have been used for decades and are based on ABA principles and can be tailored to any age group and used across settings (Majeika, 2020). While this piece has focused on the combined use of the Premack Principle and visual supports to motivate students and increase appropriate behavior, it is worth noting that the first/then contingency can also be done verbally. For students with autism and developmental disabilities who are strong visual learners, the concrete use of visual supports can be instrumental to motivating student success.

References

Cooper, C., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2020). Applied behavior analysis. Merrill.

Herrod, J.L., Snyder, S.K, Hart, J.B., Franz, Sarah J., & Ayres, K.M.. (2023). Applications of the Premack Principle: A review of the literature. Behavior Modification, pp. 219-246.

Majeika, C.E. (2020). Supporting student behavior through behavioral contracting. Teaching Exceptional Children, 53-2, pp. 132-139.

Rousseau, F. (1971). Behavioral programming in the re-education school. The Information Dissemination Office, Tennessee Department of Mental Health.

Taylor, J.T., & Hill, D. (2017). Using daily behavior report cards during extended school year services for young students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 40(4).

Miss Kitty Advice Column

Miss Kitty

Dear Miss Kitty:

Shortly after the Thanksgiving break, my classroom paraprofessional had to resign due to serious illness. I had worked with her for over 10 years in our self-contained cross categorical class at the primary school, and she was a joy to work with because she was positive, optimistic, and built good relationships with our students. Before she left, I asked our administrator if she could hire someone a few weeks before so the new person could come in and observe and see how my previous paraprofessional worked with students.

Our administrator could not find anyone to fill the position, partly because our salaries are not comparable to other districts in the area. As a result, my new paraprofessional was hired shortly after Thanksgiving, and I was not given any input into her hiring. She was hired on Monday and started in my room on Tuesday with no training.

I am trying to be positive, but she was with me until the holiday break and seems to just want to sit and do nothing except argue with the students. I talked to her several times before the holiday break about being positive, but she did not change her behavior. I hoped when she came back in January things would be better but that has not been the case. If anything is true, she is worse. I can’t give her anything to do because she will either not do it or do it wrong. The last straw for me is that she told another teacher that I needed to be harder on my students. I don’t know how much longer I can take this.

Miserable Meghan

Dear Miserable Meghan:

I am so sorry to hear about the loss of your previous paraprofessional, and I am sure that alone has been rough for you because she sounds like she was everything you could have wanted in a para. It is also sad you were left out of the hiring process because it would have been very beneficial for you, the para, and the administrator. That said, with the serious shortages we are seeing it is getting more difficult to find people willing to accept positions, so your administrator was faced with a tough decision—hire someone or not fill the vacancy. Your administrator wanted you to have a para, and may have thought she was doing the right thing.

What can you do now:

- Talk to your administrator about the situation. See if there are any new applicants for positions. Find out what the district is doing to recruit others. Maybe there is another applicant and the one you currently have could be transferred to a position where she does not work directly with children.

- Remember also that your para came into your classroom with no training at all so talk to the administrator about whether this individual can participate in training on appropriate behavioral interventions. DEBH, in some states, provides training at little or no cost to paraprofessionals so it would be great if you could get her registered for training. If you know of trainings taking place either virtually or in person, attend with your paraprofessional so you are both hearing about the same interventions and can talk about them objectively.

- Suggest to your administrator there be a workshop for everyone in the building about positive behavioral interventions. Maybe there could also be short discussions at all-faculty meetings.

- Many schools have book discussions where they choose a book on behavioral interventions. Ask your administrator whether that would be possible and whether the paraprofessional could be involved.

- At the same time, you can have a heart-to heart discussion with her about positive behavioral interventions. Pick an intervention a week, and talk to her informally about it.

- Equally important to these suggestions, is to look for anything the paraprofessional is doing correctly and let her know what she did and why it was helpful to you and to the students. You must look for what she does positively. Give her the benefit of the doubt. Maybe she doesn’t know what to do or she is afraid of failing. Offer to help her. Just as we provide supportive assistance to students, she may also need it.

- If all of this is not successful, then I believe you will have to talk to the administrator, see whether she has a contract and for how long it is. Talk about the need for an evaluation for her that lets her know if changes are not made, she will not be able to continue in the position.

I am wishing you the best in this second semester, and I hope that approaching this with actions that are designed to give her a chance to grow will result in positive change.

Bridging Dreams, not Snatching Them: A Practical Guide to Transition Planning for Minority Students with EBD in High School

LaSheba W. Hilliard, Ed.D.

University of Memphis

Navigating high school is a transformative journey for any student, but for those with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders (EBD), the path can be uniquely challenging. These students face unique challenges, including societal prejudices, limited access to resources, and, often, a lack of adequate support systems. Nevertheless, through intentional, comprehensive, and inclusive strategies, we can champion the educational success and career readiness of minority students with EBD disabilities. Transition is crucial in creating a thriving learning environment for minoritized students with EBD in secondary education. The transition from high school to post-secondary education or employment is critical for all students but is particularly significant for minority students with disabilities (Trainor et al., 2020). These students often need more support and resources to facilitate a smooth transition. Transition plans should focus on developing academic skills, social competencies, and self-determination, which are fundamental for successful transition and readiness. Family involvement, school-community collaboration, and culturally responsive practices can further support the transition and readiness of minority students with disabilities. Transition planning for minority students with EBD should involve specific components to address their unique needs and ensure a successful shift from school to post-school life. Here are some key components to consider:

1. Cultivating Empathy and Understanding:

Understanding the individual experiences and challenges faced by minority students with EBD is the foundational pillar for effective teaching and support. Cultivating empathy among educators involves acknowledging the diverse backgrounds and life circumstances that may contribute to EBD. Teachers should strive to create a classroom environment that is not only academically stimulating but also emotionally supportive.

Action Steps:

Cultural Competence Training: Conduct regular training sessions to enhance educators' cultural competence, fostering an understanding of the intersectionality of minority identities and emotional and behavioral disorders.

Individualized Support Plans: Collaborate with special education teams to develop individualized support plans that consider both the cultural background and specific emotional and behavioral needs of each student.

Open Communication Channels: Facilitate open communication between teachers, students, and their families. Create a space where students feel comfortable expressing their needs and concerns, fostering a sense of trust and support.

2. Individualized Transition Plans:

Tailoring transition plans to the unique needs of each student with EBD is essential for ensuring a successful journey through high school and beyond. Individualized planning considers the cultural, academic, and emotional aspects of a student's identity.

Action Steps:

Collaborative Goal Setting: Engage in collaborative goal-setting sessions with students, their families, and relevant support services. Goals should be realistic, measurable, and aligned with the student's aspirations, considering both cultural and individual factors.

Life Skills Development: Integrate life skills development into the curriculum, focusing on essential skills such as communication, self-advocacy, and decision-making. This prepares students for independent living and future success. It is important to note that supporting minoritized students in developing self-advocacy skills and decision-making will empower them to express their needs, rights, and aspirations (Gilson et al., 2021). Life skills development plays a crucial role in transition planning for individuals with disabilities.

Career Exploration and Guidance: Facilitate exposure to various career paths through internships, job shadowing, and career guidance counseling. Tailor these experiences to align with the student's interests and abilities, considering the potential impact of cultural factors on career choices.

3. Family and Community Engagement:

Building a solid network of support involves actively engaging families and the broader community in the transition planning process. Collaboration between educators, families, and community resources creates a holistic student support system.

Action Steps:

Family Engagement: Actively involve families in the transition process by organizing workshops, support groups, and regular check-ins. Families play a crucial role in reinforcing strategies learned in school.

Community Partnerships: Forge partnerships with mental health organizations, community centers, and local agencies to provide additional resources and support. Community engagement can offer a holistic approach to addressing the multifaceted needs of students.

In conclusion, Bridging Dreams, not Snatching Them: A Practical Guide to Transition Planning for Minority Students with EBD in High School stands as a beacon of hope and guidance for educators committed to fostering an inclusive and supportive environment for students with EBD in a high school. As educators embrace culturally competent teaching practices, individualized transition planning, and active family and community engagement, they contribute to a transformative journey for minority students. The discussed components recognize the unique challenges faced by students in secondary education, particularly those from minority backgrounds, and provide actionable strategies to bridge the gap toward academic and personal success. According to researcher and education advocate Gloria Ladson-Billings, "Culturally relevant teaching is using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, and performance styles of diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them" (Ladson-Billings, 1995, p. 469). This sentiment underscores the importance of acknowledging and incorporating cultural diversity into educational practices and transition planning. As educators implement the principles above, they not only nurture academic growth but also contribute to the holistic development of minority students. The vision of success becomes attainable when a collaborative and culturally responsive approach is taken, bridging the dreams of minority students and ensuring that the transition through secondary education becomes a stepping stone toward a future filled with possibilities.

References

Gilson, C. B., Thompson, C. G., Ingles, K. E., Stein, K. E., Wang, N., & Nygaard, M. A. (2021). The job coaching academy for transition educators: A preliminary evaluation. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44(3), 148–160. https://doi-org.ezproxy.memphis.edu/10.1177/2165143420958607

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But That's Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675

Trainor, A. A., Carter, E. W., Karpur, A., Martin, J. E., Mazzotti, V. L., Morningstar, M. E., Newman, L., & Rojewski, J. W. (2020). A Framework for Research in Transition: Identifying Important Areas and Intersections for Future Study. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 43(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143419864551

Powell v. School Board of Volusia County, Florida (2023)

Mitchell Yell

In today’s newsletter, I will discuss an interesting case out of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th, Circuit, Powell v. School Board of Volusia County, Florida (2023). The case is available on the 11th Circuit website. It is of special interest because the school district prevailed at the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, but was vacated (i.e., overturned) and remanded (i.e., sent back to the lower court) at the circuit court in light of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Perez v. Sturgis, 2023.

In this class action suit, the parents of students with disabilities asserted that the Volusia County School District used exclusions and disciplinary removals as consequences for disability-related behaviors exhibited by their children. Examples of such actions included sending their children home early, instructing the parents to keep their children at home even when they were not suspended, improperly using out-of-school suspension, and initiating removal procedures under a Florida law known as the Baker Act, thus discriminating against their children on the basis of their disability.

The parents filed a $50 million lawsuit against the school district under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act in the federal district court for the middle district of Florida. The parents sought injunctive relief (i.e., asking the court to require the school district to stop the use of discipline in this manner), compensatory damages, and punitive relief.

The federal district court dismissed their case because the plaintiffs had failed to exhaust their administrative remedies (e.g., a due process hearing) under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The district court held that the plaintiffs could not bypass the administrative requirements of the IDEA by framing their allegations under other laws (e.g., Section 504).

A few months after the district court’s ruling was announced on November 9, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Perez v. Sturgis (2023). In this case, the High Court ruled that parents do not need to exhaust their administrative remedies under the IDEA if the lawsuit seeks damages that the IDEA does not provide. Because courts have routinely held that the IDEA does not include monetary damages, suits looking for monetary damages do not have to exhaust their administrative remedies under the Perez rule.

The parents refiled the claim with the 11th Circuit Court, which vacated and remanded the case to the district court for a new ruling in light of the Perez decision. This decision means that after the Perez ruling, school districts may have cases that were settled on exhaustion grounds relitigated even though the Perez ruling came after the case was first settled.

In the Powell case, it is likely that the Volusia school district may find itself litigating a lawsuit thought to be over. For sure, it will be a high bar for parents to convince the court to award monetary damages under Section 504 and the ADA. Nonetheless, this possibility will likely lead to more litigation.