Behavior Today - Council For Children with Behavioral Disorders Newsletter

From the President’s Desk

Dear Members and Friends of DEBH,

Writing this last address to you as my community of individuals committed to the education and welfare of children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and am pleased to introduce the new LOGO of CEC’s Division of Emotional and Behavioral Health.

The 2020-2021 year is one we will each remember for different reasons. Some highlights I reflect on: I believe we learned how to expand our outreach and impact for many more individuals – especially those disadvantaged and traditionally unable to participate in live and travel-based conferences. I believe we saw amazing service, leadership, and scholarship mobilized in profoundly different ways. I also believe we saw a social justice movement occur that has changed how we engage with those around us.

I know that many of us have experienced deep physical and emotional losses this year, and I hope each of us has found our support people to help move us through those times. I also hope we enter into the 2021-2022 academic year full of compassion for ourselves and others. Let this be the year emotional and behavioral challenges, disorders, disabilities, and ultimately health, are the central focus of our communities and our educational efforts. Best wishes and thank you for efforts on behalf of children and youth with EBD, their caregivers, educators, and families.

Be well.

Kimberly Vannest, PhD

Chair and Professor,

Department of Education University of Vermont

DEBH President

Upcoming Nominations

The Chairperson of the Committee on Nominations and Elections, DEBH (formerly CCBD), requests nominations for the following offices:

- Vice President, four-year term of office, serving as Vice-President, President-elect, President, and Past-President for one year each. (four-year term)

- International Member-at-Large (two-year term)

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Member-at-Large (two-year term)

- Nominations and Elections Committee Member (three-year term)

- Representative A to the General Assembly (two-year term)

Any other DEBH member may nominate any DEBH member. All terms of office begin July 1, 2022. To obtain a job description for any office, please contact the Chairperson.

To nominate, send the Chairperson a letter stating the nominee’s name, mailing address, and the name of the office for which they are nominated. The nominator must sign the letter and include his/her CEC membership number. The deadline for receipt of nominations is October 1, 2021.

Upon receipt of the nomination, the Chairperson will contact each nominee to solicit four copies of the following supporting material:

- Statement from nominee, separate from the nominator’s letter, agreeing to be nominated.

- CEC membership number of the nominee, to validate DEBH membership.

- Three-part statement that presents, in 1,000 words or fewer, the following: issues for the Division of Emotional and Behavioral Health (may involve students, professionals, or other issues), responses needed to deal with issues identified, and how the nominee, if elected, can work on the DEBH Executive Committee in responding to these issues.

- Condensed resume or vita (maximum of three pages).

- A ballot statement describing nominee’s qualifications, perspectives, and/or goals. This will be included in the ballot verbatim, and length must not exceed 100 words. Chairperson may require rewriting or may edit ballot statements to meet word limit.

- Photograph for the ballot, website, and social media.

The deadline for receipt of supporting material from nominees is October 1, 2021.

The Nominations & Elections Committee will evaluate supporting materials and recommend a slate of at least two nominees and usually no more than three nominees to the DEBH Executive Committee. DEBH members will receive a ballot early next year for electing officers. Results will be announced in the Annual Business Meeting at the CEC Convention, in the DEBH newsletter Behavior Today, and/or via email. Send nominations and supporting material to: [email protected]

Please feel free to reach out to Kimberly Vannest, Chair, DEBH Nominations and Election Committee, with any questions at [email protected].

Dear Miss Kitty: Advice Column

Dear Miss Kitty:

I have had the worst year ever in my 15 years of teaching. We were remote part of the year, hybrid part of the year, and in person the last 3 weeks of school. I teach a self-contained cross categorical class with 8 students and our school was short staffed so I was expected to teach all day and to teach two hours online after the students who came to school left. Then, during the last three weeks, our school was short substitutes so I would have to take my 3rd grade students in my cross categorical class into a general education classroom and teach both groups. I understand that my principal was under a lot of pressure, and he operated in crisis mode all year.

I am seriously thinking of leaving the profession because I will have the same principal, and I believe he will continue to pressure me to take on more responsibilities. Should I look for a position away from teaching?

Have Had it Henry

Dear Have Had it Henry:

My hat is off to you, Henry, for persevering through this school year. I am so sorry to hear about all of the challenges you encountered, and I know you are worried about what to do. You have to be exhausted so I would like to encourage you to take the month of June and July to de-stress and see how you feel at the end of July. Here are some ways you might want to recharge your battery:

1. Celebrate that you did it. You accomplished a great deal, and pat yourself on the back for all the work you were able to complete.

2. Do something that you have been wanting to do for fun. Maybe there is a favorite place you have wanted to hike or you have a list of books you want to enjoy.

3. Carve some time each day to go to the gym or take a walk.

4. Spend some quality time with your family and friends doing things that are enjoyable.

5. Look for a workshop that you would like to take and join with other educators who may invigorate you.

6. Consciously reduce your screen time. You spent a lot of time looking at a screen this year so walk away from it for some periods of time.

7. If you like to write, try to journal your thoughts about what it was like to teach during the pandemic. You may find this very cathartic.

8. Rev up your creative juices by painting or drawing.

9. Write a note to your students and parents checking to see how they are doing and thanking them for their cooperation.

10. Think of something fun you would like to plan for your students in the fall.

Always remember the positive difference you make and use the month of June and July for a lot of reflection. I hope you will recharge and be ready to stay in education.

Wishing you a happy summer!

Sincerely,

Spring Branch Independent School District v. O.W. (961 F.3d 78, 5th Cir. 2020)

Mitchell Yell

In 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit issued an interesting ruling in a case titled Spring Branch Independent School District v. O.W. Because the ruling was out of a circuit court, also called an appellate court, it is very influential. The only court higher than the circuit courts is the U.S. Supreme Court. The fifth circuit rulings set precedent for all the U.S. District Courts in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

The case involved a gifted student with ADHD, mood disorders, anxiety, and oppositional defiant disorder enrolled in the Spring Branch Independent School District in Texas. As soon O.W. was enrolled in the school district, he began to exhibit problem behavior. O.W.’s mother made an oral request that an evaluation be conducted for special education eligibility. The school district refused to conduct an evaluation. The student’s parents paid for a private evaluation of O.W. During this time, the school district agreed that O.W. was eligible under Section 504 and would receive accommodations. Despite receiving these accommodations, O.W. continued to exhibit problems behaviors, fail classes, and was suspended from school on a number of occasions. About 5 months after O.W.’s enrollment, personnel at his school agreed to conduct a special education evaluation after he assaulted a teacher. While an evaluation was being conducted, the school district officials offered O.W. placement in a special program, to which O.W.’s parents agreed. After the evaluation was completed, O.W. was determined eligible under the category of emotionally disturbed and an IEP was developed that included academic and behavioral accommodations. Close to a month after finding O.W. eligible for services, the school district offered special education services at the Adaptive Behavior Program at Ridgecrest Elementary School. Despite guidance in O.W.’s IEP to avoid power struggles and to provide him access to a “cooling off” area, the staff members at Ridgecrest used timeouts, physical restraints, isolations, and police interventions. The final police intervention proved to be so traumatic to O.W. that he was placed on shorted school days for the final month of school.

O.W.’s parents decided to enroll him at a private school, Fusion Academy, for the upcoming school year (2015-2016). They notified the school district in August, 2015 of this decision. O.W.’s parents requested a hearing in which they asserted the school district had failed to provide O.W. with a FAPE as required by the IDEA. A hearing was held and the IHO ruled that (a) the Spring Branch ISD had failed in its Child Find Duty under the IDEA, (b) the IEP developed for O.W. was not appropriate, and (c) the IEP was not properly implemented because the use of physical restraints, timeouts, and police interventions that were being used were not consistent with the interventions in O.W.’s IEP. The IHO ordered the school district to reimburse O.W.’s parents for 2 years of tuition at the Fusion Academy, because this private school offered appropriate services to O.W., attorneys for Spring Branch ISD brought suit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas alleging that the IHO’s ruling was inappropriate.

The federal district court ruled that because the district took over four months to begin the special education evaluations, despite evidence that O.W. was eligible for services, the finding of the IHO regarding the child find violation was upheld. When examining the IHO ruling that the school district failed to implement the IEP, the judge noted that O.W.’s IEP focused on positive behavioral supports and teaching of replacement behaviors and did not include the use of timeout, physical restraint, and police interventions which was used as procedures to address O.W.’s problem behavior. The judge also noted that a failure to implement a student’s IEP may deny the student a FAPE if the failure amounts to a substantial failure or material failure and more than a minor discrepancy. The federal district court judge found the school district’s failure to implement O.W.’s IEP was substantial and denied FAPE, thus affirming this aspect of the IHO’s ruling. The judge also upheld the IHO’s award of two years of tuition reimbursement to O.W.’s parents. The district court decision was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld the ruling that the school district had failed in its child find duties and had not provided a FAPE because of a failure to implement O.W.’s IEP. The federal appellate court remanded the award of remedies back to the circuit court.

This ruling is very significant to administrators and teachers of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. First, the child find duties of the IDEA require that if special education personnel know, or should have known (the so-called KOSHK standard), a student may have a disability and be in need of special education services, school district personnel have an affirmative duty to strongly consider conducting a special education evaluation. This is also true if general education interventions, perhaps as part of a schoolwide MTSS system, are not successfully addressing a student’s problem behaviors. Second, if a student is determined eligible under the IDEA, his or her IEP must address problem behaviors using positive behavioral interventions and supports and teach appropriate replacement behaviors. Third, if there is a crises intervention plan to be used in the case of extremely disruptive or dangerous behavior, the plan should be included in the student’s IEP and only be used if there is an actual crisis. Fourth, it is extremely important that all involved staff understand and properly implement the student’s IEP. Failing to implement the IEP may be a denial of FAPE.

Becoming a Guardian

Gwendolyn K. Deger, Ph.D.

Death is never an easy subject to talk about…especially when it needs to be discussed with, and for, an individual with a disability. As parents and guardians, we often want to shelter our children from the worst experiences in life, but what happens when the person who protected the individual through life dies?

Future life planning is hard, but it is essential when caring for an individual with a disability. Although we feel that we will outlive our individual, it is often the opposite situation where they outlive you. This is something that is not discussed enough in transition planning for life after high school in practice or in preparation programs. My experience as a special educator got turned upside down after the passing of my mother in 2004 and my father in 2015.

My mom had passed away in 2004 from a rare Stage IV bile duct and liver cancer while being pregnant with my youngest brother. Her sacrifice on getting treatment, saved my youngest brother, but left a void in our lives. My father then raised his eleven children (yes you read that correctly) on his own for eleven years. His diligence in caring for my brother with Down syndrome, focused my interest in becoming a special educator and established my bond with my brother.

My dad was able to get my brother services so he could live as independent as possible. I was fortunate to be able to work as a family supports specialist while finishing my undergraduate degree with my own family and other families in the community. This gave me a lot of perspective in how hard families work outside of schools to ensure their child gets the services they need. However, the one thing my dad never wanted to talk about was future planning in the event my dad died.

Fast forward eleven years, my dad passed away suddenly, leaving eight of my siblings without someone to support them at home. My brothers and sisters came together immediately as a family and were a huge support for the two oldest (my sister and myself), who had to begin to think about life after dad for everyone. First and foremost on our minds were making the best decisions on who would be the guardians of my siblings under the age of 18. Second was helping my siblings who were young adults (after high school) find financial and housing supports. Third was managing my dad’s estate.

My dad did not have a notarized will, which required us to petition the county courts to allow my sister and I to become guardians of our youngest siblings. There, we had to reveal all we knew about my siblings’ disabilities and how we were qualified, and capable, to care for them. Once guardianship was awarded, then the difficult decision of moving my brother to live with me and my family was made. This meant he would need to move almost three hours from the rest of his other brothers and sisters. It also meant a mountain of paperwork and phone calls to move school districts and services from one county to another. It further meant redirecting social security survivor’s benefits to a new representative payee. None of these things were ever taught to me in my college courses on transition but were a huge need to help my brother successfully transition to a new area.

I was fortunate in having a supportive team in preparing my brother for transitioning to the new school district, for setting up his family support services and respites, and for getting his financial benefits in place for him. The one thing I did not focus on though was grief counseling for him.

It took my brother a while to begin the grief process, and it unfortunately took me longer to recognize the symptoms. My brother, when he was getting ready to graduate from high school, began having difficulty in events or activities that surrounded loss. For example, losing in video games. He began acting out, running away from teachers or family support personnel, or lashing out at others. Although I knew something was wrong, I didn’t understand it was grief until I worked with some crisis intervention specialists. They helped me piece together the events all had one theme in common (even though they were all very different incidents). After that, my brother began to get the mental health services he needed, and he has been doing wonderfully since then.

As a guardian, I learned a lot about the need for advocacy and for future planning. As a special educator, I used what I experienced to help my students and their families cope through difficult situations. As a teacher of special educators, I teach about how grief and trauma can impact an individual in different ways, and by communicating with families, we can support our individuals to become their best selves.

Using the Five Love Languages to Address Challenging Behavior: A Proactive Classroom Management Approach

Adrain N. Christopher

Department of Collaborative Special Education, Alabama A & M University

One of the most stressful components of a teacher’s job involves managing challenging behavior. Teachers cite lack of preparation, including introduction to effective strategies, in addressing challenging behaviors as another layer of stress they encounter (Allday et. al, 2012), forcing them to implement reactive classroom management (responding only after challenging behavior occurs) as opposed to using proactive classroom management (having an established plan that outlines the teacher’s desired expectations and how they plan to address challenging behavior). Some would argue that due to this lack of preparation, teachers tend to lean towards classroom management practices that are degrading and not culturally sustaining, which typically contributes to challenging behavior being exhibited (Ladson-Billings, 2014).

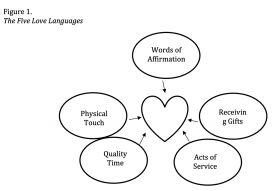

All behavior, challenging or otherwise, is inevitable in the classroom and always serves a purpose (Wheeler & Richey, 2014). In recent years, research has expanded to include social-emotional needs of students as a means of explaining challenging behavior, and the utilization of culturally sustaining practices to address challenging behavior. Culturally sustaining practices, like specific praise and active supervision, considers and incorporates the needs of all students, creates opportunities for teachers to have meaningful interactions with every student by giving them specific feedback on behavioral expectations (Haydon, et. al, 2019; Haydon & Musti-Rao, 2011) and are grounded in building positive student-teacher relationships. Evertson and Weinstein (2006) note that building trust between teachers and students is an essential tenet of proactive classroom management and is instrumental in establishing and maintaining effective classrooms. A rapport does not occur without some facilitated effort by the teacher. In fact, it only occurs when the teacher takes calculated steps to understand the students as individuals, including their social-emotional needs, specifically what they need to feel loved or what Chapman and Campbell (2016) refer to as their love language. Understanding the students love language can give teachers insight as to why students exhibit the behaviors they do. Additionally, when authentic student-teacher relationships are formed and a genuine comprehension and implementation of the students’ love language occurs, teachers can be intentional about planning and adjusting plans to cater to these emotional needs and ultimately address challenging behavior.

Note: Adapted from Discovering the 5 Love Languages at School Grades 1-6 (p. 35), by G. Chapman and D. M. Freed, 2015, Northfield Publishing. Copyright 2015 by Gary Chapman and D. M. Freed. Adapted with permission.

Like specific praise statements, words of affirmation are honest and encouraging words delivered to a child (verbally or written) and makes them feel loved (Chapman & Freed, 2015). Children whose primary love language is words of affirmation feel secure when their efforts, no matter how minimal, are affirmed instead of criticized (Chapman and Campbell, 2016) and are more likely to continue engaging in behaviors that result in them receiving words of affirmation. Words of affirmation, like specific praise statements, yields the best results when genuine encouraging words commend the individual student for exhibiting specific behaviors.

For students who feel loved when they receive gifts, they prefer receiving some type of tangible item (e.g., toys) as a symbol of love. However, the student is not often impressed by the cost of the gift but rather what the gift represents. To a student whose primary love language is receiving gifts, the gifts are positive representations that inform them they are appreciated and loved (Chapman & Freed, 2015). There is an old saying, “It’s not the gift, but it’s the thought that counts”, Chapman and Freed (2015) note that a student feels more loved when the gift is personal and relatable, not expensive and extravagant, and therefore continue to exhibit the behavior that gives them access to receiving gifts.

Acts of service entails intentionally doing something for someone that is unexpected (Chapman & Freed, 2015). Acts of service can be an unclear love language for students to identify and can involve a host of frustrating behaviors for teachers. Teachers often unconsciously perform acts of service for students, and in return, the students can sometimes demonstrate an attitude of entitlement and expectation instead of gratefulness. Students may not know and understand their primary love language is acts of service because they view the acts the teacher does as a part of the teacher’s job. For this viewpoint to be combatted, the acts of service should be intentionally catered to the needs and desires of the student so there is no doubt by the student that the teacher intends to show him/her love by completing this service for them.

Loving a student whose primary love language is quality time requires a vast amount of work for a teacher for a few reasons. First, there is only one teacher, in some cases, and several students, and second, the students whose primary love language is quality time desire plenty of it (Chapman & Freed, 2015). While this can be an overwhelming fete for teachers, it is not impossible. When teachers spend time developing a deeper connection with their students whose primary love language is quality time, the student feels more loved and secure because the teacher intentionally took the time to get to know them and what they need; therefore, the students become more willing to be compliant with the expectations of the teacher.

The last of the five love languages, physical touch, can be the most difficult love language to fulfil because of the misperceptions associated with it when it is inappropriately exhibited. Some teachers tend to shy away from this love language to avoid misunderstandings about their intentions. While their concerns are understandable, teachers should understand that a student whose primary love language is physical touch, will not relinquish their need to feel loved because the teacher is uncomfortable. Physical touch is natural and is the first way a child feels loved. When teachers refuse appropriate physical touch in the classroom, it deprives the students who need it of the safe, warm, inclusive environment that they desire (Chapman & Freed, 2015) and forces them to demonstrate behaviors that will give them access to the physical touch they crave. Teachers should find safe appropriate ways to give access to students whose love language is physical touch if they truly desire to have a safe nurturing classroom and ultimately address challenging behavior.

When teachers practice reactive classroom management, they are in essence “flying blind” in their classrooms, and they may not be equipped to adjust in the moment to address challenging behavior. Teachers can refuse to succumb to demeaning reactive classroom management strategies by implementing culturally sustaining practices like specific praise, active supervision, and the five love languages. Love is a universal language spoken by all students. Understanding and catering to how students’ need to be loved and what they need to feel secure is necessary when establishing trust and building a rapport with students. When a student knows that a teacher loves them, has their best interest at heart, and that they can depend on them, there is nothing that student will not do for that teacher and that is the essence of proactive classroom management and establishing an effective classroom.

References

Allday, R. A., Hinkson-Lee, K., Hudson, T., Neilsen-Gatti, S., Kleinke, A., & Russel, C. S. (2012). Training general educators to increase behavior-specific praise: Effects on students with EBD. Behavioral Disorders, 37(2), 87-98.

Chapman, G., & Campbell, R. (2016). The 5 Love Languages/5 Love Languages for Men/5 Love Languages of Teenagers/5 Love Languages of Children. Moody.

Chapman, G. D., & Freed, D. M. (2015). Discovering the 5 Love Languages at School: Grades 1-6: Lessons that Promote Academic Excellence and Connections for Life. Northfield.

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Classroom management as a field of inquiry. Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues, 3(1), 16.

Haydon, T., Hunter, W., & Scott, T. M. (2019). Active supervision: Preventing behavioral problems before they occur. Beyond Behavior, 28(1), 29-35.

Haydon, T., & Musti-Rao, S. (2011). Effective use of behavior-specific praise: A middle school case study. Beyond Behavior, 20(2), 31-39.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74-84.

Wheeler, J. J., & Richey, D. D. (2014). Behavior management: Principles and practices of positive behavior supports. Pearson.

Creating Classrooms of Belonging: Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy as Habits of Practice

Lindsay Beatty, M.Ed., Kendra Kelley, M.Ed. & Lianna Pizzo, Ph.D.

University of Massachusetts Boston

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy (CSP) sees students’ cultural practices as an asset in the classroom (Paris & Alim, 2014). Rooted in Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995, 2009, 2014), CSP seeks to nurture the many identities students have in the world (e.g., racial, linguistic, gender, class). Schools that embrace CST connect culture and classroom patterns towards wider acceptance of the range of student emotions and behaviors, reducing the need for behavior interventions. CST also examines oppressive messaging and systems to foster critical thinking and social emotional development (Nash et al., 2021).

The aim of CST is to cultivate teaching practices that allow students to regularly express the many versions of themselves. Below is a list of strategies that can be incorporated in your daily work that draw upon the research on cognitive and social emotional benefits for CST.

- Make relationships with students and families the foundation of your teaching. Take time throughout the day for sharing and listening. Provide students with time to talk with one another about their interests and lives outside of school. Share about yourself and your experiences. Ask what students feel they need for the day and the week ahead. Ask families their preferred communication mode and follow through with regular, respectful contact.

- Create a classroom culture in which students have autonomy over choices and their own learning. Structure learning activities to honor students working at their own pace and provide choice over topics of study. For example, students could determine their own topics for an opinion writing assignment or could choose from a menu of options to work on during math or reading workshop time.

- Learn about the funds of knowledge your students bring to the classroom and build upon the expertise they bring from their lived experiences (Gonzalez et al., 2005). Routinely make space for students to contribute their expertise. For example, when introducing a measurement, geometry, or engineering concept, take time to ask about students’ experiences measuring, building, cooking or using tools at home.

- Challenge traditional definitions and roles of “teacher” “student” and “classroom” and expand these to be more inclusive, interactional, and fluid. Include families and members of the community as experts by inviting guests to the classroom. Bring your students out of the classroom to explore the school grounds and community. For example, students could interview school crossing guards to learn about their work and the streets around the school. These interviews could connect to history and social studies as well as math and mapping.

- Make intentional and inclusive language choices in your instruction and daily routines, recognizing the inextricable link between language and culture. Present vocabulary in the languages used by your students and their families. Include multilingual text in these languages around your classroom such as “Can you help me with ______?/¿ Puedes ayudarme con ______?” Encourage students to use their preferred language(s) in academic and social interactions and model this yourself when possible.

- Validate the many different identities of students in your classroom by ensuring your curriculum is representative of your students (mirrors) while also providing students with opportunities to learn about and appreciate diversity (windows) (Sims Bishop, 1990). Seek out literature and media which illustrate a variety of identities and life experiences (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, social class, ability, family structure, nationality, language, communities). Encourage students to think about whether a book was a window or a mirror for them, asking “How did you connect with this story/character? How did this story/character help you to understand the experiences of others?”

- Approach curriculum with a critical/historical lens, recognizing that curriculum has historically marginalized/oppressed those who do not align with the dominant culture (e.g., white, English speaking, middle class, typically developing, adhering to gender binary). Analyze individual lesson plans, units, and materials and ask yourself, “Who is included/represented? How are they portrayed? Who is centered? Who is left out?” Engage students in this process and in gathering with their families and community members missing material and knowledge (e.g., books, movies, music, photographs, artifacts, stories).

- Develop and enact multiple assessment opportunities that are authentic, interactive, and multimodal. Use photos and videos of student work as evidence of student progress towards learning goals. Encourage students to document their work in preferred modalities (e.g., photograph, video, audio, work sample), including their own reflections. For example, a student could take a video of themselves explaining how they solved a word problem as evidence of mathematical reasoning.

- Make self-reflection a priority and use these reflections to inform your practice and guide your decision-making through the other principles on this list. Ask yourself, What am I noticing? Why is this important? What can I do to better prioritize cultural assets in the classroom? For example, you might notice the books in your classroom do not reflect a range of experiences or the cultures of your students. You can decide to meet with families and with colleagues to gather materials relevant for your group of students.

- Advocate for social and racial justice in your school and work to dismantle systems of oppression within/beyond the system of education, supporting your students to do the same. Make justice and agency a part of your daily classroom discourse. For example, in a unit on “The Myth of the First Thanksgiving” students may reveal their variety of understandings about colonization in North America and think critically about their school’s Columbus Day. Your class may elect to start a school-wide campaign about the history of Columbus and to change the holiday and focus to Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

By incorporating routines that create a space for identity expression and connection to community in our classrooms, it becomes easy to engage in CST as a habit of practice. These habits allow us to honor children (Nash et al., 2021) in all their representations and ways of being.

Author’s Note

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lindsay Beatty, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, 100 William T. Morrissey Blvd. Boston, MA 02125-3393. [email protected]

References

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge. Routledge Member of the Taylor and Francis Group.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 465-491.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84, 74-84.

Nash, K., Polson, B., & Glover, C. (2021). Education for the human soul: Culturally sustaining pedagogies and the legacy of love that guides us. In Nash, Glover, & Polson (Eds.)., Toward Culturally Sustaining Teaching: Early Childhood Educators Honor Children with Practices for Equity and Change. Routledge.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85-100.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1 (3), ix–xi.

Advancing EBD Advocacy:

Lessons from the Autistic Self-Advocacy1 Movement

Martha L. Hernandez, M.S.Ed. & Michelle M. Cumming, Ph.D.

Florida International University

Over the past several decades, there has been a call for a grassroots movement to advocate for students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) and bring the necessary sensitivity and understanding of their needs to the forefront. For instance, Bradley and colleagues in 2008 voiced frustration with the lack of organized and vocal advocacy groups for students with EBD who could unite to push for needed improvements (e.g., school-based services, federal definition). Although certain organizations currently exist that are dedicated to advancing the success of children and youth with EBD, such as the Council for Children with Behavior Disorders (CCBD; https://debh.exceptionalchildren.org) and Advocacy for E.B.D. (https://advocacyforebd.org), parent/guardian- and self-advocacy groups continue to remain scarce.

Other disability communities have benefited from powerful and well-established advocacy groups, such as the Learning Disabilities Association of America (LDA; https://ldaamerica.org/) and the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN; https://autisticadvocacy.org/). These groups have been instrumental in increasing disability awareness, shaping policies, and increasing funding. Given the overlap between autism and EBD in terms of emotional and behavioral characteristics (Matson & Goldin, 2013), we draw upon lessons learned from the autistic advocacy movement to offer insight into ways to build and focus grassroots advocacy for students with EBD.

Lesson 1. Center Students’ Voices

Bascom, an autistic self-advocate involved in the disability rights movement, argued that central to advocacy is centering the voices of individuals with disabilities. For instance, acknowledging that individuals with autism have “valid, legitimate, and important things to say about [their] lives and about issues that affect [them] collectively” (2012, p. 365) resulted in (a) the inclusion of individuals with autism in policy development (e.g., Ari Ne’eman’s appointment to the National Council on Disability); (b) shifted the focus from combating autism to acceptance (e.g., ASAN’s efforts changed the name of the Combating Autism Act to the Autism Collaboration, Accountability, Research, Education, and Support Act of 2014); and (c) higher visibility of the experiences of disabled individuals (e.g., DJ Savarese, a nonverbal poet, co-directed DEEJ, a film about his experiences). Therefore, when building EBD advocacy, the voices of individuals with EBD must be solicited (e.g., focus groups, surveys) and included (e.g., goal and issue prioritization).

Lesson 2. Focus on the Person Versus the Disability

Durbin-Westby (Bascom, 2012), an autistic self-advocate and founder of Autism Acceptance Day, underscored the importance of viewing a person with a disability as a person with a mind, body, and goals. There has been a long history in the United States of individuals with disabilities being denied rights (e.g., institutionalized, incarcerated) solely based on their disability (Gerber, 2011). With a shift from disability to person perspective, the rights of individuals with autism have improved, such that autism has gained acceptance as a neurological difference that can be supported and accommodated. Thus, EBD advocacy should focus on the student with EBD as a person first to help shift ongoing stigmatization related to special education classification and mental health disorders (Kauffman & Badar, 2013), as well as the use of less effective or harmful responses to behavior (e.g., punishment, physical restraint, expulsions, incarcerations; Kauffman & Landrum, 2018).

Lesson 3: Movement Towards Inclusion

Many autistic self-advocates and their parents have called for full integration into society and an end to institutional segregation based on disability (Bascom, 2012). Although a greater percentage of students with autism are now educated in neighborhood schools than in the past, this is an ongoing point of advocacy and overlaps with the needs of students with EBD, as both groups are at risk for segregation. Of approximately 350,000 K-12 students with EBD, 35.5% are in self-contained settings (e.g., therapeutic day schools, separate classes in neighborhood schools) for more than 60% of their day (Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, 2017). Even when placed in these settings designed to provide intensive and targeted supports, they continue to make limited progress (Bradley et al., 2008). Therefore, EBD advocacy should emphasize inclusion advancements in public school settings, focusing on evidence-based support and services, appropriate accommodations and modifications, and quality special education teacher training.

Lesson 4: Consider Cultural and Linguistic Diverse Backgrounds

Although the autism movement provides valuable insight into powerful and effective advocacy, it is distinct in that autism tends to be viewed as a white, privileged, and middle-class disability, while EBD is disproportionally applied to marginalized groups from low socioeconomic backgrounds (Skiba et al., 2008). For instance, Black, economically disadvantaged males tend to be overrepresented in EBD and are often placed in more restrictive settings (Skiba et al., 2008). Thus, due to the significant differences in the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic status of students with EBD, advocacy should address identification disproportionality, classification stigma, and the importance of embedding culturally sustaining practices in classrooms to address student needs. Overall, the advancement of an EBD focused grassroots advocacy movement can be a powerful means to improve the rights, services, and outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, graduation rates, later employment) of students with EBD.

References

Bascom, J. Ed. (2012). Loud hands speaking: Autistic people, speaking. The Autistic

Press.

Bradley, R., Doolittle, J., & Bartolotta, R. (2008). Building on the data and adding to

the discussion: the experiences and outcomes of students with emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Education, 17(1), 4-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-007-9058-6

Gerber, M. M. (2017). A History of Special Education. In J. M. Kauffman & D. P.

Hallahan (Eds.), Handbook of special education (2nd ed., pp. 3-15). Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315517698-2

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Public Law 108-446, 118 Stat. 2647 et

seq. 2004).

Kauffman, J. M., & Badar, J. (2013). How we might make special education for

students with emotional and behavioral disorders less stigmatizing. Behavioral Disorders, 39(1), 16-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874291303900103

Kauffman, J. M., & Landrum, T. J. (2018). Characteristics of emotional and behavioral

disorders of children and youth (11th ed.). Pearson.

Matson, J. L., & Goldin, R. L. (2013). Comorbidity and autism: Trends, topics, and

future directions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(10), 1228-1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.003

Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. (2018). 40th Annual Report

to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. https://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2018/parts-b-c/40th-arc-f…

Skiba, R. J., Simmons, A. B., Ritter, S., Gibb, A. C., Rausch, M. K., Cuadrado, J., & Chung, C. (2008). Achieving equity in special education and current challenges. Exceptional Children, 74(3), 264-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290807400301

Creating a Forum for Student Voice for CLD Students with EBD

William Hunter, Ed.D. Associate Professor of Special Education, Alycia M. Taylor, Ed.D. Clinical Professor, Keishana L. Barnes, Ed.M. Clinical Professor

University of Memphis

The historic Brown vs. Board of Education, 1954, and later the creation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), both served as direct responses to inequitable educational services (Yell, 2019). Yet, nearly fifty years after the initial passing of IDEA, the educational system remains unjust and without equity, especially for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students with disabilities. As ramifications from the 2020 national peaceful protest movements and COVID-19 pandemic generated conversations associated with the broader fight against systemic racism, institutions such as medical facilities, police departments, and PK-12 school systems came under criticism (Combe, 2020). While PK-12 schools have been criticized in various areas for (the lack of) instructional equity for CLD students, that critique has also applied to special education more broadly. Although the special education system was designed to support all students, the disproportionate placement of Black students in subjective special education categories serves as evidence that this goal has not been achieved (Skiba, 2013).

When students identify as CLD and have low socio-economic status, they are challenged less in their coursework and are more likely to be referred for special education (Gonzalez, 2001). Moreover, there is an over-representation of CLD students in special education (Zhang & Katsiyannis, 2020), specifically with emotional behavioral disorders (EBD) (Artiles, 2017). This intersectional identity is connected to many adverse experiences, and students who fit this profile may “experience low self-esteem, relationship issues, increased levels of stress, and powerlessness” (Hurless & Kong, 2021). Therefore, to support the emotional and educational success of this population of students, as well combat these negative realities, it is vital that teachers create culturally responsive and sustaining classrooms (Ladson-Billings 2014; Paris, 2012), which center student voice and promote interactive learning, in both inclusive and self-contained settings.

Establishing an Effective Classroom Environment

Teachers play a crucial role in the quality of educational opportunities for students (Gay, 1997). Unfortunately, teachers tend to allow the label of “EBD” to adversely affect their perceptions and expectations for student success (Bianco, 2005), often viewing student behavior as problematic (Gay, 2002), and choosing authoritarian dominance of students rather than engaging them in academic learning. Which, in turn, negatively impacts students’ overall success. For teachers to create and maintain a classroom culture where CLD students with EBD can thrive, they must first critically examine their own beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions, being careful not to allow potential biases to impede their instruction. It is, then, essential for teachers to elevate student voice to increase student engagement, give them more ownership of their education, and improve their overall academic success (Fisher & Frey, 2014).

Amplifying Student Voice

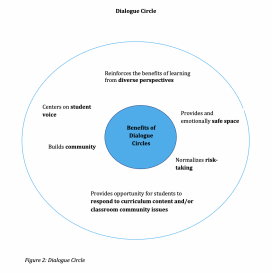

The classroom should be a safe space where students not only gain knowledge, but also feel free to express themselves through student voice. Student voice is defined as referring to “the values, opinions, beliefs, perspectives, and cultural backgrounds” of students (www.edglossary.com). When student voice is amplified, the classroom becomes a place where students feel valued, can engage more critically in curriculum, and are more likely to actively engage in the learning process (Friere, 1998), leading to more positive Classroom Emotional Climate (CEC) and, thus, more adherence to social and behavioral classroom expectations (Reyes, et. al., 2012). The purpose of this paper is to provide teachers resources to amplify and integrate student voice within the classroom for students with EBD. The following strategies serve as important steps for teachers to take to encourage student voice by strengthening relationships through classroom management onboarding (CMO-b), cultivating students’ sense of belonging through establishing dialogue circles, and increasing engagement through flexible grouping.

Strategies to Integrate Student Voice

Classroom Management Onboarding. While planning for instruction, teachers may create a classroom management on-boarding (CMO-b) plan that solicits student background information and clearly communicates classroom guidelines and expectations (Hunter et al., 2021). With this student-centered approach, teachers can begin to build authentic and mutually respectful relationships with students and, in turn, establish preventative measures for disruptive behaviors (Hunter et al., 2021) often associated with students with EBD. Figure 1 is a modified version of CMO-b. Please see Figure 1.

Dialogue Circles. Prior to instruction, teachers may consider beginning class with a dialogue circle to foster unity in the classroom. This strategy is essential for CLD students with EBD as they can share their thoughts, reactions, and ideas concerning a common topic in an organized, shared space (Parker & Bickmore, 2020). Such spaces create a forum for discussion about current events within the classroom, school, community, and world. Figure 2 details benefits of dialogue circles. Please see Figure 2.

Flexible Grouping. After the establishment of CMO-b and dialogue circles, the authors recommend the option of flexible grouping. During instruction, teachers may utilize flexible grouping to promote opportunities for positive feedback while supporting student learning (Maheady et al., 2020). Schools tend to have difficulty successfully supporting students with EBD to display certain interpersonal skills (Hofmann & Muller, 2020). Therefore, flexible grouping is advantageous for this group of students as they can collaborate with their peers in multi-party learning groups (Hunter, 2020), often leading to improved learning gains (Hunter et al., 2015). Figure 3 is an example lesson plan for teachers of students with EBD in middle/high school and can be adjusted based on grade/skill level. Please see Figure 3.

|

Subject: Social Studies Grade: 9th Date: Tuesday, September 14, 2021 Classroom Setting (Inclusive): 30 total students/5 students with IEPs Lesson Title: Civil Rights Movement Standards: Objective: Using the Number Heads Together (NHT) strategy, TSW answer 10 evidence-based questions to analyze main and secondary ideas with 80% accuracy. Materials: Handheld dry erase boards, dry erase markers, dry erasers, 1 die, large dry erase board w/projector or interactive white board, Microsoft PowerPoint, YouTube |

| Background Information |

| Prior to this lesson, the students engaged in learning activities including within the (classroom dialogue circle) connected to the same standards. This lesson is planned as Day 2 of a 5-day sequence. During Day 1, the teacher used informational resources that focused on the Civil Rights Movement. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s website contains lessons/reading material (The Ohio State University College of Arts and Sciences, n.d.). |

| Anticipatory Set |

| Do Now/Bell Ringer Activity: After viewing a short clip from Monday’s lesson (snippet of Fannie Lou Hamer’s Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party Speech a). TSW respond to three questions, citing evidence from the video (YouTube). |

| Interactive Instruction |

| After facilitating student responses, TTW respond to and provide rationale for answers to questions related to the YouTube video presented in the anticipatory set. |

|

| Independent Practice |

| Exit slip consisting of 10 questions requiring students to analyze evidence from text and making inferences based on Day One’s reading. |

Note. TSW = The students will; TTW = The teacher will.

as This is Fannie Lou Hamer’s, unprecedented speech given on behalf of the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party (MDFP). In her address, she described the violent barriers Black Americans faced when attempting to vote.

Conclusion

Creating a forum for student voice within K-12 classrooms is one way to ensure equitable education for CLD students is achieved. The strategies of strengthening relationships through classroom management onboarding (CMO-b), cultivating students’ sense of belonging through establishing dialogue circles, and increasing engagement through flexible grouping are potential resources to integrate and amplify the voices of CLD students with EBD within K-12 classrooms. Although schools may have struggled to support students with EBD with their interpersonal skill development in the past, that does not mean that their voice should be minimized within classroom settings. Thinking positive, in terms of the goal high school graduation leading to post-secondary options, K-12 settings should be a forum for students with EBD to engage in meaningful conversations, incorporating their voice in the classroom while addressing potential challenges with interpersonal relationships/dialogue amongst peers and adults.

References

Bianco, M. (2005). The effects of disability labels on special education and general education teachers' referrals for gifted programs. Learning Disability Quarterly, 28(4), 285-293.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Talking and listening. Educational Leadership, 72(4), 18-23.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gay, G. (2002). Culturally responsive teaching in special education for ethnically diverse students: setting the stage. Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(6), 613-629.

Gonzalez, V. (2001). The role of socioeconomic and sociocultural factors in language minority children’s development: An ecological research view. Bilingual Research Journal, 25(1&2), 1-30.

Hofmann, V., & Muller, C.M (2020). Peer influence aggression at school: How vulnerable are higher risk adolescents? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426620917225

Hunter, W. (2020). Flexible grouping for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavior Today Newsletter, 36(4), 16-20.

Hunter, W., Maheady, L., Jasper, A., Williamson, R., Murley, R., & Stratton, E. (2015). Numbered heads together as a tier 1 instructional strategy in multitiered systems of support. Education and Treatment of Children, 38(3), 345-362.

Hurless, N., & Kong, N. Y. (2021). Trauma-informed strategies for culturally diverse students diagnosed with emotional and behavioral disorders. Intervention in School & Clinic, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451221994814

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74-84.

Parker, C., & Bickmore, K. (2020). Classroom peace circles: Teachers’ professional learning and implementation of restorative dialogue. Teaching and Teacher Education, 95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103129

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Reyes, M., Brackett, M., Rivers, S., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 700–712. doi: 10.1037/a0027268

Skiba, R. (2013). CCBD'S position summary on federal policy on disproportionality in special education. Behavioral Disorders, 38(2), 108-120.

Yell, M., & Katsiyannis, A. (2019). The Supreme Court and special education. Intervention in School and Clinic, 54(5), 311-318. doi: 10.1177/1053451218819256

Zhang, D., & Katsiyannis, A. (2020). Minority representation in special education: A persistent challenge. Remedial and Special education, 23, 180-187.